Exclusive

ISRAEL’S STRATEGIC FUTURE

The Final Report of Project Daniel

April 2004

FOREWORD by

Professor

Louis René Beres, Chair

Further to the issuance of

The National Security Strategy of the

United States of America on

September 20, 2002, US President George W. Bush launched Operation Iraqi Freedom

in March of the following year. The results of that war, still substantially

unclear at the time of this writing, derive from a greatly broadened American

assertion of the right of unilateral preemption. A conceptual and implemented right, it expands

the binding and well-established customary prerogative of “Anticipatory

Self-Defense”a under international law. Although there have as yet been no

subsequent legal codifications of this new American expansion, the precedent established by the world’s

only remaining Great Power is certain to impact the actual policy behavior of

other states.

Not surprisingly, many in the international community have criticized this new

policy. Yet history is replete with examples where nations have correctly reserved unto

themselves the right of preemption when they have determined that their vital

national interests, or very existence, were under threat.

In short, whether or not the presumptively expanded right of

striking-first as self-defense will soon become a generally accepted norm of

authoritative international law, this right will, in practice, likely acquire

enhanced credibility and legitimacy. Even if the broadened idea of anticipatory

self-defense does not achieve the status of a peremptory norm as defined at

Article 53 of The Vienna

Convention on the Law of Treaties,b

it will be invoked more often by certain imperiled states. In this connection,

the growing spread of weapons of mass destruction throughout the world – now

exclusively to unstable and undemocratic states – fully underscores the

broadened doctrine.

Israel’s Strategic Future: the Final Report of Project Daniel, was

completed in mid-January 2003, several months before commencement of Operation

Iraqi Freedom. Nothing associated with America’s 2003 war against Saddam

Hussein’s regime in Iraq or the still ongoing conflict within that fragmented

country suggests a changed reality for Israel and the Middle East. On the

contrary, the “lessons” of Operation Iraqi Freedom demonstrate not only that our

Final Report remains valid, but that its validity has been significantly

enhanced. Today, more than ever before, the State of Israel – a state so small

that it could fit twice into America’s Lake Michigan – must include appropriate

preemption options in its overall defense strategy. Vastly more vulnerable to

catastrophic first-strike aggressions than the United States, Israel must

prepare now for existential harms in every available fashion. Consistent with

The National Security Strategy of the

United States of America and

the strategic objectives of Operation Iraqi Freedom, Israel has an inherent right to defend itself without

first absorbing biological and/or nuclear attacks. This is true irrespective of

the cumulative outcome of Operation Iraqi Freedom or of particular criticisms

now directed toward the United States.

Project Daniel began with the assumption

that Israel’s security environment must be appraised continuously, and that the

threat of irrational state and nonstate enemies armed with WMD assets represents

the single most urgent danger to the country’s survival. Early on in our deliberations, however, we (“The

Group”) agreed that while the overall impact of this threat was extraordinarily

high, its probability was considerably less than that of WMD assaults from

rational enemy quarters. Reflecting this judgment, we concluded

that Israel’s main focus must now be on preventing a coalition of Arab states and/or

Iran from coming into possession of weapons of mass destruction. Preferably, we

urged this objective be pursued while Israel continues with its present policy of

deliberate ambiguity regarding its own nuclear status. We also concluded that

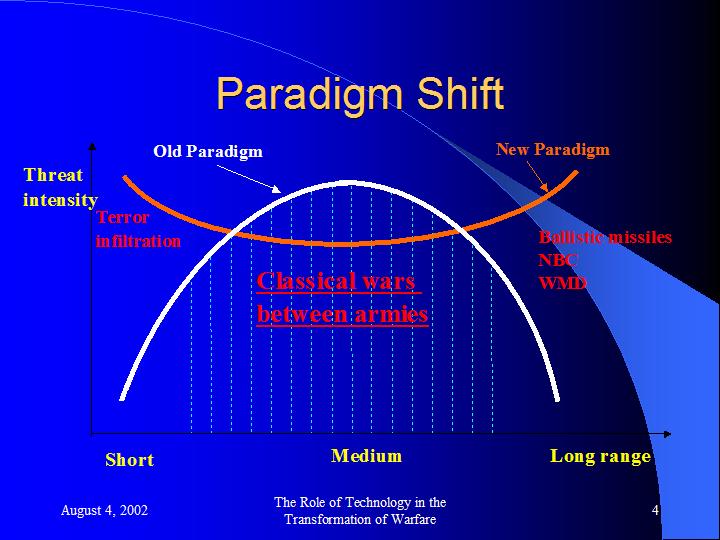

the classic paradigm of war between national armies could become less predictive

in the developing Middle East, and that an Israeli “paradigm shift” is therefore

required. This shift in orientation and resources would place new emphases on

short-range threats (terrorism) and long-range threats (ballistic missiles and

weapons of mass destruction). Here we also recommended a corresponding reduction

in the resources Israel should now allocate to classical warfighting scenarios.

Today, at the end of April 2004 – 15 months after our presentation of

Israel’s Strategic Future

to Prime Minister Ariel Sharon – we strongly reaffirm these recommendations.

Our Group notes emphatically that Israel should avoid non-conventional exchanges with

enemy states wherever possible. It surely is not in Israel’s interest to

engage these states in WMD warfare if other options exist, but rather to create

conditions wherein such forms of conflict need never take place.

Israel’s Strategic Future

does not instruct how to “win” a war in a WMD Middle-East environment. Rather,

it describes what we, its authors, consider the necessary, realistic and

optimally efficient conditions for nonbelligerence toward Israel in the region.

Altogether unchanged by Operation Iraqi Freedom, these conditions include a

coherent and comprehensive Israeli doctrine for deterrence, defense, warfighting and

preemption.

Our precise strategic theses, validated

by the 2003 Iraq War and its aftermath, are intended to aid policymakers in

bringing stability and predictability to a troubled region.

Following the main body of

Israel’s Strategic Future,

which remains exactly as it was completed originally in January 2003, a

newly-prepared “Addendum” will bring the reader up-to-date with current

circumstances and allow him or her to better understand the Final Report in full

and proper historical context. It is strongly suggested, therefore, that the

reader consider this brief annex as an integral part of

Israel’s Strategic Future.

Louis

René Beres, Ph.D.

Professor of International Law

Purdue University

Chair of Project Daniel

Notes

a

The right

of anticipatory self-defense under international law was established by Hugo

Grotius in

Book II of The Law of War and Peace (1625). Here, Grotius indicates that

self-defense is permissible not only after an attack has already been suffered,

but also in advance – “where the deed may be anticipated”. Or as he says later

in the same chapter: “It be lawful to kill him who is preparing to kill...” A

similar argument is offered by Samuel Pufendorf in his treatise, On the Duty

of Man and Citizen According to Natural Law (1672). The customary right of

anticipatory self-defense has its modern origins in the Caroline incident, which

concerned the unsuccessful rebellion of 1837 in Upper Canada against British

rule (a rebellion that elicited sympathy and support in the American border

states). Following this event, the serious threat of an armed attack has

generally been taken to justify militarily defensive action. (See J. Moore, A

Digest of International Law 409 (1906)). Today some scholars maintain that

the customary right of anticipatory self-defense expressed by the Caroline has

been overridden by the specific language at Article 51 of the UN Charter. In

this view, Article 51 fashions a new and far more restrictive statement of

self-defense, one that does rely on the literal qualifications contained in the

phrase, “...if an armed attack occurs”. This interpretation ignores, however,

that international law cannot logically compel a state to wait until it absorbs

a devastating or even lethal first strike before acting to protect itself. And

the argument against the restrictive view of self-defense is reinforced by the

well-documented weakness of the Security Council in undertaking collective

security action against a prospective aggressor. For supportive positions on the

particular reasonableness of anticipatory self-defense in the nuclear age, see:

Louis Henkin, et.al., International Law: Cases and Materials 933 (1980)

(Citing Wolfgang Friedmann, The Threat of Total Destruction and Self-Defense

259-60 (1964); Joseph M. Sweeney et. al., The International Legal System:

Cases and Materials 1460-61 (3rd ed., 1988) (citing Myres McDougal, The

Soviet-Cuban Quarantine and Self-Defense, 57, American Journal of

International Law 597, 598 (1963)).

b Concluded at Vienna, May 23, 1969, Entered into force,

January 27, 1988, 1155 U.N.T.S. 331; 1969 U.N.J.Y.B. 140; 1980 U.K.T.S. 58, Cmnd

7964; reprinted in 8 I.L.M. 679 (1969).

Israel’s Strategic Future

Project Daniel

Final Report

Prepared Especially for Presentation to the Hon. Ariel Sharon

Prime Minister of the State of Israel

January 16, 2003

Project Daniel is a private and informed effort to identify the overriding

existential threats to Israel and their prospective remedies. These remedies

must be both plausible (capable of achievement) and productive. With this in

mind, the Group met in both Washington DC and New York City on several

occasions during 2002. In the periods between meetings,

members of the Group regularly exchanged information. The result of this effort

is conveyed in the following Final Report: Israel's Strategic Future. The

perspectives expressed in this document are those of the individual members, and

do not necessarily reflect views of any institution or government. Our hope is

that Project Daniel’s unique configuration of member background and experience

will contribute to the strengthening of US-Israel strategic relations and to the

ongoing debate over how Israel should best respond to existential threats to its

national security.

The

Group is comprised of the following individual members:

Professor Louis René

Beres, Chair, USA

Naaman Belkind, Former Assistant to the

Israeli Deputy Minister of Defense for Special Means, Israel

Maj. Gen. (Res.), Israeli Air Force/Professor Isaac Ben-Israel,

Israel

Dr. Rand H. Fishbein, Former

Professional Staff Member, US Senate Appropriations Committee, and former

Special Assistant for National Security Affairs to Senator Daniel K. Inouye, USA

Dr. Adir Pridor, Lt. Col. (Ret.), Israeli Air Force; Former

Head of Military Analyses, RAFAEL, Israel

Fmr. MK./Col. (Res.), Israeli Air Force,

Yoash Tsiddon-Chatto,

Israel

Executive Summary

-

Considering issues

of both probability and disutility (harms), the principal existential

threat to Israel at the present time is a conventional war mounted against

it by a coalition of Arab states and/or Iran.

-

Israel is also

endangered (presently or

potentially) by Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD), nuclear and/or biological

weapons that could be used against it either by enemy first-strikes or via

escalation from conventional war. Israel’s particular vulnerability to

such weapons is a consequence of its tiny area, its high population

density and its national infrastructure concentrations. We recommend,

therefore:

-

Israel do whatever

possible to prevent an enemy coalition from being formed and from coming

into possession of WMD. This could include pertinent preemptive strikes

(conventional) against enemy WMD development, manufacturing, storage,

control and deployment centers. This recommendation is consistent both with

longstanding international law regarding “anticipatory self-defense” and

with the newly-stated defense policy of The United States of America.

-

Israel should

continue with present policy of ambiguity regarding its own nuclear status.

This would help to prevent any legitimization of WMD in the Middle East. It

is possible, however, that in the future Israel would be well-advised to

proceed beyond nuclear ambiguity to certain limited forms of disclosure.

This would be the case only if enemy (state and/or non-state) nuclearization

had not been prevented.

-

Israel should

provide all constructive support to the United States-led War Against Terror

(WAT). It must insist upon aiding the American objective to

prevent/eliminate WMD among rogue states and terror groups in the Middle

East. There is a clear coincidence of interest between Israel and the United

States in matters of security and counter-terrorism.

-

Israel

must do everything within its means to prevent a Middle Eastern rogue state

or terror group from attaining WMD status. Irrespective of its policy on

nuclear ambiguity vs. disclosure, Israel will not be able to endure unless

it continues to maintain a credible, secure and decisive nuclear deterrent

alongside a multi-layered anti-missile defense. This recognizable

(second-strike) retaliatory force should be fashioned with the capacity to

destroy some 15 high-value targets scattered widely over pertinent

enemy states in the Middle East. The overriding priority of Israel’s nuclear

deterrent force must always be that it preserves the country’s security

without ever having to be fired against any target. The primary point of

Israel’s nuclear forces must always be deterrence ex ante, not

revenge ex post.

-

If WMD status were attained by any

Middle Eastern rogue state or coalition of states, the probability of

joint-enemy conventional attack against Israel would be raised

considerably. Faced with adversaries who now might believe themselves

shielded under a WMD “umbrella”, Israel would have to do the following:

-

Maintain its

conventional forces at full war-waging strength and with a decisive

qualitative edge. Hopefully this would be accomplished with full

material support from the United States, whose interests would be

coincident with Israel’s interests.

-

Adapt its planning priorities and

budgetary requirements to the “paradigm shift” described later in this

Report. In this connection, Israel is urged to reduce the priority it

assigns to conventional warfighting without impairing its undisputed

superiority against any plausible enemy coalition.

-

The Group is aware

that many of its strategic recommendations are contingent upon adequate

funding. Should the substantial funds needed by Israel to deal with

so-called “Low Intensity” and Long-Range WMD threats be sought via

increased taxation, it could threaten Israel’s economy and (ironically)

undermine Israel’s security in other ways. To deal purposefully with these

threats (threats which are delineated in this Report’s following

presentation of “paradigm shift”), Israel’s government must trim all

nonproductive costs and seek to encourage dramatic increases in

productivity. The resultant rise in per capita GNP could allow the needed

increase for Israel’s national defense.

The Existential Threat to Israel

In

an age of Total War, Israel must remain fully aware of threats to its very

continuance as a viable state. With such awareness, Israel has always recognized

an imperative to seek peace through negotiation and diplomatic processes

wherever possible. This imperative, codified at the United Nations Charter and

in multiple authoritative sources of international law, shall always remain the

guiding orientation of Israel’s foreign policy.

When

Israel’s search for peaceful settlement of disputes is not reciprocated,

however, it must be prepared to deal with a wide range of existential threats.

Taken literally, the idea of an existential threat implies harms that portend

complete annihilation or the disappearance of the state. The Group feels,

however, that certain forms of both conventional and unconventional attack

against large Israeli civilian concentrations would constitute an existential

threat. Although such forms of aggression are clearly criminalized by

longstanding rules of Humanitarian International Law, Israel must:

-

Acknowledge that these rules have often been

ignored by certain Middle Eastern adversaries; and

-

Take appropriate protective steps involving

deterrence, active defenses, passive defenses, and preemption.

Regarding preemption, international law has long allowed for states to initiate

forceful measures when there exists “imminent danger” of aggression. This norm

of “anticipatory self-defense” has been expanded and strongly reinforced by

President Bush’s recent issuance of The National Security Strategy of the

United States of America. Released on September 20, 2002, this document

asserts, inter alia, that traditional concepts of deterrence will not work

against an enemy “whose avowed tactics are wanton destruction and the targeting

of innocents...”, and that “We must adapt the concept of imminent threat to the

capabilities and objectives of today’s adversaries.” This “adaptation” means

nothing less than striking first where an emergent threat to the United States

is judged to be sufficiently unacceptable.

As

Israel is substantially less defensible and more vulnerable than the United

States of America, its particular right to resort to anticipatory self-defense

under threat of identifiable existential harm is beyond legal question.

Moreover, as Israel’s ties to the United States are strong and unambiguous, so

too are the strategic interests of the two countries tightly interwoven.

Certain WMD attacks upon Israeli cities could be genuinely existential. For

example, biological or nuclear attacks upon Tel Aviv that would kill many

thousands of Israeli citizens could have profound and dire consequences on the

continued viability of the country.

A

recent report by the Washington-based Heritage Foundation examined the effects

of an Iraqi WMD attack on Tel Aviv.1 In one scenario, a single Iraqi missile

carrying 500 kilograms of botulinum would kill approximately 50,000 individuals.

In another scenario, an Iraqi missile fitted with 450 kilograms of VX nerve gas

would kill 43,000 people. If left to develop nuclear warheads, Iraqi missiles

could kill hundreds of thousands of Israelis.

The

Group notes three distinct but interrelated existential threats:

-

Biological/Nuclear (BN) threats from states;

-

BN threats from terror organizations; and

-

BN threats from combined efforts of states

and terror organizations.

To

the extent that certain Arab states and Iran are allowed to develop WMD

capabilities, Israel may have to deal with an anonymous attack scenario; that

is, a situation wherein the attacking state does not identify itself and where

Israeli identification of the perpetrator is problematic. Overall, there is a

“force multiplier” issue for Israel to face, a situation in which multiple

attacks upon Israel from various configurations of state and non-state

adversaries create a pattern of harms that is greater than the sum of its parts.

Regarding effective deterrence of such situations, the Group feels that Israel

must identify explicitly, and early on, all enemy Arab states and Iran, as

subject to massive Israeli reprisal in the event of BN attacks upon Israel. In

doing so, the Israeli deterrent posture would closely mirror that of the United

States towards the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

Since the terror attacks of September 11, 2001, the US has made it clear that it

reserves the right to use all available weapons in response to any attack upon

its soil by an adversary using Weapons of Mass Destruction. (The Bush

Administration told Congress, on December 11, 2002, that it is now the policy of

the United States to use “overwhelming force”, including nuclear weapons, if

chemical or biological weapons are used against America or its military forces.

The threats are contained in a six-page document identified as National

Strategy to Combat Weapons of Mass Destruction). Israel, in our view, should

follow a similar policy.

Existential threats to Israel may be exacerbated further by Arab/Iranian leaders

whose actions, by Western standards, might be deemed irrational. Faced with

enemy leaders who do not value national and/or personal self-preservation more

highly than any other preference or combination of preferences, Israeli

deterrence could be immobilized and security could be based largely upon the

success or lack of success of prior preemption efforts.

Under such circumstances, a policy of Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD) which was

once obtained between the United States and the Soviet Union would not work

between Israel and its Arab/Iranian adversaries. Rather, the Group understands

that Israel must prevent its enemies from acquiring BN status and that any

notion of BN “parity” between Israel and its enemies would be intolerable. The

ratios of physical size 800:1, population 55:1, and political clout 22:1 UN

votes between Israel and its enemies, and some of the latter’s’ utterly zero-sum

concept of conflict with Israel (a concept currently allowing for no possibility

of compromise and reconciliation) means that Israel’s survival is contingent

upon avoiding parity at all costs. With this in mind, we strongly believe that

Israel immediately adopt – with highest priority – a policy of preemption with

respect to enemy existential threats. Such a policy could also enhance Israeli

deterrence to the extent that it would reveal the country’s expressed

willingness and resolve to act as needed.

Recognizing the close

partnership and overlapping interests between Israel and the United States, the

Group fully supports the ongoing American War Against Terror. In this connection

we urge full cooperation and mutuality between Jerusalem and Washington

regarding communication of intentions. If for any reason the United States

should decide against exercising preemption options against certain developing

weapons of mass destruction, Israel must reserve for itself the unhindered

prerogative to undertake its own anticipatory self-defense operations.

The

Group began its deliberations with the following concern: Israel faces the

hazard of a suicide-bomber in macrocosm. Here, in this scenario, an enemy Arab

state and/or Iran would act against Israel without ordinary regard for

retaliatory consequences. In the fashion of the individual suicide bomber who

acts without fear of personal consequences – indeed, who welcomes the most

extreme personal consequence, which is death – an enemy Arab state and/or Iran

would launch WMD attacks against Israel with full knowledge and expectation of

overwhelming Israeli reprisals. The conclusion to be drawn from this scenario is

that deterrence vis-à-vis “suicide states” would have been immobilized by

enemy irrationality and that Israel’s only recourse in such circumstances would

have been appropriate forms of preemption.

The

Group is also concerned about a particular variant of this scenario wherein an

enemy state or combination of states does not actually seek or welcome massive

Israeli reprisals, but – because of the vast demographic advantage over Israel –

is willing to accept huge losses because Israel’s losses would be relatively

even greater. If the enemy state or states were to calculate that it could

afford a 1-to-1 exchange with Israel, it/they could literally compel Israel’s

losses to be in the high existential range. The prospect of such an enemy

calculation underscores Israel’s ultra sensitivity to enemy weapons of mass

destruction and its imperative to adopt a policy of preemption whenever

possible.

Rationale

The

Group recognizes a basic asymmetry between Israel and the Arab/Iranian world.

This asymmetry concerns attitudes toward the overall desirability of peace; the

absence of democratic regimes in the Arab/Iranian world; the acceptability of

terror as a legitimate weapon by the Arab/Iranian world; the zero-sum conception

of conflict vis-à-vis Israel held by some states of the Arab/Iranian

world; the overwhelming demographic advantage of the Arab/Iranian world; and the

greater tendency of the Arab/Iranian world to make mistakes in strategic

calculations. Taken as a whole, these asymmetries point toward an intemperate

Arab/Iranian plan for protracted war against Israel that is wedded to an

unquenchable desire by some to develop Weapons of Mass Destruction for use in this war.

In

view of the above-mentioned asymmetries, non-conventional exchanges between

Israel and adversary states in the Middle East must be avoided. It is not in

Israel’s interests ever to engage in WMD warfare with these adversary states.

Therefore; Israel must maintain conventional supremacy in the region. This will

be indispensable to maintaining the threshold of WMD warfare at the highest

possible level.

Paradigm Shift

The

classic paradigm of war between national armies is becoming less relevant in the

present Middle East. In time, it can be made more efficient for Israel to

increase the emphasis on high-tech solutions (thereby expending fewer

resources).

Traditionally, short-range threats (terrorism) and long-range threats (ballistic

missiles and WMD) have been under-evaluated.

The

strategic paradigm for Israel must now shift to meet the expanding threats from

terrorism and long-range WMD attacks. In doing so, of course, there must be a

corresponding reduction in the resources Israel can devote to classical

warfighting.

Modern technology should allow Israel to reduce its defense expenditure while

maintaining or even enhancing effectiveness and lethality in classical

warfighting. Critical to this transformation in warfighting doctrine are a

range of new technologies such as a drastic increase in weapons’ lethality (ton

x miles per target destroyed) achieved through increased range, precision,

warhead efficiency; EW and other defenses; reduced IR and RF signatures and on

course + final percussion (data link) feed-back. Efficient use of sophisticated

weapons is only possible if pre- and post-strike, real time intelligence, both

tactical and strategic is available and accurate, and if strike command, control

& communications are computer interfaced with real time intelligence (C4I).

The

Group understands that terror and WMD threats reflect a relative weakness in

both “flanks” of the allocation graph. Resources should be allocated to

technologies against those who conduct terror as well as the infrastructures

that support them. Such effective technologies are already in existence.

The Group recalls the following relevant

technologies against strategic threats: Anti-ballistic missiles; warning

satellites; strike UAVs (BPLI); long-range deployment forces; and “long-arm”

capability (to be discussed in greater detail further on in this Report).

The paradigm shift has worldwide

implications.

As stated above the Group feels that:

-

Israel must do whatever is needed to

keep the Middle East non-BN, including conventional preemptive strikes

against enemy facilities for developing and producing BN weapons;

-

Israel should not stimulate or

provoke or in any way legitimize enemy development of BN weapons; it

should, therefore maintain its current posture of deliberate ambiguity as

long as possible;

-

Israel must strongly support the

American War Against Terror (WAT), urging

that destruction and prevention of nonconventional capabilities in the Arab/Iranian

Middle East

remain Washington’s overriding objective. In the event of an

American/Israeli failure to prevent BN deployment in a

hostile country or

countries in the Middle East, Israel will have to maintain and declare a

deterrent nuclear arsenal. This would necessarily involve precise and

identifiable steps to fully convince enemy states of Israel’s willingness

and capacity to use its nuclear weapons.

The Group is concerned about time-lapses in

Arab/Iranian nuclearization. Some current thinking points to short durations

needed for an enemy state to achieve a given level of nuclear capability, thus

creating a sense of real urgency. Others have preferred long estimates, thereby

identifying emergent enemy nuclear threats as still far-off in the future. We

suspect that Arab/Iranian development stages will be rather long (that is,

consistent with parallel processes in other states and regions of the world),

while phases of acquisition and building-up of arsenals after the first pieces

have been put into place will be relatively short. We suggest, therefore, that

Israeli policy not refer to “a period wherein some Arab states possess just a

few nuclear devices”. Such a period would inevitably be rather brief, and Israel

could not dwell productively on having sufficient time, under such

circumstances, for long processes of response.

The Group identifies the following list of

phases with typical expected durations.

Some, but not all of these phases, may be

simultaneous:

-

Develop a (laboratory) nuclear fission device – 10

years

-

Develop a fusion device (having fission technology) –

10 years

-

Prepare strategic materials for a nuclear device – 10

years

-

Develop an air bomb (weapon system) – 8 years

-

Develop a long-range missile – 12 years

-

Fit a nuclear warhead into a missile – 8 years

-

Build an arsenal of 100 bombs (after the first) – 4

years

-

Build an arsenal of 100 nuclear missiles (after the

first) – 4 years

-

Build a distributed system of missile launchers – 5

years

-

Operate a fleet of nuclear missile submarines – 12

years

The above list of phases offers a rough

idea of the amount of time Israel might have for preparations at each declared

and verifiable stage of Arab/Iranian nuclear build-up.

The Group also offers informed judgments

concerning the types of weapons for Israeli preemptive operations. We reject the

argument that nuclear weapons are necessarily required for preemption of enemy

nuclear capability. Conventional means are generally much more effective than

nuclear devices for this purpose. Even if nuclear weapons are fully available

for preemption, and even if their use would be consistent with authoritative

international law, conventional weapons would be preferable wherever possible

against emergent enemy nuclear capabilities.

The Group recognizes there is also the

additional advantage of acting preemptively against enemy BN capabilities

without escalating to a BN war in the Middle East. The tools for preemptive

operations would be novel, diverse and purposeful; for example, long-range

aircraft with appropriate support for derived missions; long-range high-level

intervention ground forces; long-endurance intelligence-collection systems;

long-endurance unmanned air-strike platforms, and so on.

The Group bears in mind that once achieving

BN status, enemy states in the Middle East region could:

-

Launch unconventional war against

Israel; or

-

Launch conventional or low-intensity

war against Israel under the counter-deterrent “umbrella” of their Weapons

of Mass Destruction. To prevent such a scenario, wherein Israel could

presumably be deterred from retaliation by threats of

unacceptably-damaging enemy counter-retaliations, Israel should maintain

its “qualitative edge” with assistance from the United States and adapt

itself to the aforementioned Paradigm Shift. Under these circumstances,

Israel must have conventional superiority against its Arab/Iranian enemies

even under cuts recommended by the paradigm shift, and its defense budget

must consistently support such needed superiority. More than ever before,

the first Basic Point in Israel’s Security Doctrine needs to be remembered

and respected: “Israel cannot afford to lose a single war.”

Conceptually, in examining the

persuasiveness of Israeli nuclear deterrence, we must distinguish sharply

between threats of enemy low- intensity/conventional attack and threats of enemy

nuclear/BN attack. But as the most serious enemy conventional attacks would be

launched against Israel by states with a backup BN capability, the

persuasiveness of Israeli nuclear deterrence will always have to be assessed

vis-à-vis enemy BN weapons.

Maintaining Israel’s Qualitative Edge

The Group underscores that Israel’s

conventional supremacy over all adversaries and combinations of adversaries must

be maintained. Israel’s qualitative edge is the only means by which it can

compensate for a fixed and irreversible quantitative inferiority. This means,

inter alia, the following expectations for the Israel Air Force (IAF):

-

Israel will have to maximize its

long-range, accurate, real-time strategic intelligence.

-

Israel will have to maximize the

credibility of its second-strike capability.

-

Israel will have to develop, test,

manufacture and deploy a BPI (Boost Phase Intercept) capability to match

the operational requirements dictated by enemy ballistic missile

capacities (performance and numbers.)

-

Israel must begin to rely heavily on

recoverable and non-recoverable UAVs, stealthy or otherwise, for such

tasks as defense suppression, decoys, EW in all of its aspects,

intelligence gathering and strike. GPS navigation must also be emphasized.

-

Israel must maximize its traditional

combat and auxiliary manned force and equip it optimally.

-

Israel will have to assume

operational responsibility for a second-strike capability, whether

deployed on land or at sea, while ensuring an essential unity of command.

The Group emphasizes that Israel must

remain in a position to win any war conventionally. In order to prevent a

nuclear Middle East, Israel needs an ever-higher level of qualitative edge.

There is, of course, a mutuality of interest here with the United States of

America.

Israel’s needed identification and funding of particular

elements that offer its forces a qualitative edge should be consistent with our

prescribed “Paradigm Shift”. As this objective has been a continuing commitment

of successive American administrations, and is also substantially dependent upon

United States support, the Group recommends that the following key questions be

researched and explored:

-

What steps should be taken to better

integrate Israel’s capabilities with validated US military requirements?

-

What constitutes a healthy industrial

base for Israel, and what is needed to ensure Israel’s ability to meet

emerging strategic threats?

-

With a declining defense budget

(expressed as a percentage of GDP), how will Israel be able to finance not

only its next generation of military systems, but also the ongoing War

Against Terror (WAT)?

-

Is restructuring needed in the

US-Israel strategic relationship?

-

How can Israel make better use of US

military assistance?

-

What can be done to eliminate some of

the current impediments to US-Israel defense trade?

-

How can Israel better assist the

United States in meeting its requirements in homeland defense,

counterterrorism and the WMD threat?

-

What strategic forces will Israel

require to meet the long-range threats to its security, and how will the

country be able to finance these forces? These may include extended-range

attack aircraft, expanded missile defense, extended aerial refueling,

long-range special ground intervention forces and enhanced space-based C4I

capability. In the best of all possible fiscal worlds, Israel would also

seek to fund a blue ocean naval presence, but this option is presently

precluded by defense budget constraints.

-

What is needed to harden Israel’s

current defensive and offensive forces to make them sufficiently

invulnerable to enemy first strikes?

-

How can Israel minimize the trade-off

between operational readiness and force modernization?

-

How should Israel readjust its

defense strategy to take into account the possibilities of an expanded US

military presence in the Middle East?

-

What should Israel conclude about

growing threats posed by particular enemy State modernizations?

-

What should Jerusalem offer

Washington in support of future US military operations in the Middle East?

-

Should there be an enhancement of

Israel’s major non-NATO status as an ally of the United States?

The group feels that it is essential for

Israel to get US support in ongoing defense projects designed to enhance

Israel’s future overall deterrence:

Israel’s Arrow missile defense system

(prime contractor IAI) involves various arrangements with US Boeing. The IAF,

which operates the Arrow, will likely meet its goal of having 200 interceptors

in inventory on schedule. Arrow managers also hope to sell their product to

certain other States; this would help Israel to reinforce its qualitative edge.

Israeli engineers are taking steps to ensure that Arrow will function alongside

American Patriot systems. The Group feels that IAF should continue working on

external and internal interoperability issues.

In its effort to create multi-layered

missile defense system architecture, it may be that Israel is already working on

an unmanned aircraft that could hunt down and kill an enemy’s mobile ballistic

missile launchers. Israeli military officials have tried to interest the

Pentagon in joining the launcher-attack project, known as boost-phase launcher

intercept (BPLI), but Washington is focused on alternative technologies. The

Group feels that Israel could do BPLI with or without US support, but gaining

such support would allow the project to move forward much more rapidly.

Enlisting US support for BPLI would represent another important step toward

maintaining Israel’s qualitative edge.

The Group believes that the United States

should participate technologically and financially in Israel’s multi-layered

missile defense efforts as fully as possible. Israel’s priorities and timetables

are especially time-urgent, and the end-product benefits of such American

participation would be shared by both countries. The Group emphasizes the

importance of multi-layered defenses for Israel – aiming longer-term at

BPI or BPLI – but affirms strongly that Israel should act preemptively before

there is a destabilizing deployment of unconventional enemy assets.

War

Against Terror

Further to the Group’s suggestions

concerning Paradigm Shift, we believe in the overriding importance, to Israel’s

security, of the ongoing, US-led War Against Terror (WAT). This War, of course,

must be fought not only at the level of the terrorist organizations directly,

but also against the various “rogue states” that support and sustain these

organizations. From the standpoint of international law, WAT is a clear

expectation and requirement for all civilized states.

In the previously-cited document, The

National Security Strategy of the United States of America (September 20,

2002), President George Bush affirms:

Our priority will be first to disrupt and destroy terrorist

organizations of global reach and attack their leadership; command, control, and

communications; material support; and finances... We will continue to encourage

our regional partners to take up a coordinated effort that isolates the

terrorists. Once the regional campaign localizes the threat to a particular

state, we will help ensure the state has the military, law enforcement,

political and financial tools necessary to finish the task.

The President continues: “While our focus

is protecting America, we know that to defeat terrorism in today’s globalized

world we need support from our allies and friends.” The Group advises that

Israel offer such support to the United States to the fullest extent possible,

and – reciprocally – that Israel seek from the United States whatever assistance

and resources that America can provide. America’s WAT is Israel’s war, and

Israel’s WAT is America’s war. The interests of our two countries in this matter

coincide completely.

Middle East stability in general, and

Israeli security in particular, will be affected by the outcome of the WAT.

Impairment of worldwide terror capabilities and enemy unconventional weapons

capabilities is linked directly to Israeli security. By moving forcefully and preemptively against

pertinent military targets, the United States would help to prevent a WMD

conflagration in the Middle East, one that could spill over outside the region.

It would also inform the world community about the need for, and lawfulness of,

similar defensive actions by the State of Israel. The Group further believes

that any such indirect benefit of the American WAT could reinforce crucial ties

between Washington and Jerusalem, strengthening various patterns of essential

mutual assistance between the two allies.

The Group agrees that victory in the WAT (a

full realization of President Bush’s stated objectives in The National

Security Strategy of the United States of America) would be an optimal

antecedent of subsequent independent actions by Israel. We understand as well

that no clear and verifiable criteria of “victory” are readily identifiable.

Rather, the WAT will necessarily be fought amidst considerable ambiguity of

outcome; therefore, it would be a mistake for Israel to await an American

victory in this theatre before committing itself to needed defensive options. In

effect, such a delaying posture by Israel would likely preclude altogether

actions needed against existential harms.

It is very likely

that after any American-led war against Saddam Hussein's Iraq, accurate

assessments of damage to Saddam's developing WMD infrastructures and associated

intellectual assets would be problematic. The objective must be to eliminate

these infrastructures and assets entirely, and to prevent any still-planned

Iraqi steps toward WMD manufacture and deployment. Moreover, a principal

objective of any US military action against Iraq must be the removal of Saddam

Hussein, although it is not by any means clear that such removal would

necessarily end all pertinent dangers emanating from that country.

In the best of circumstances for

Israel, US armed forces will succeed in neutralizing both Saddam’s developing WMD

infrastructures/associated intellectual assets and Saddam himself. Here, depending upon:

-

Informed post-war assessments of

Iraq’s remaining WMD capacities;

-

Its remaining capability to develop

or acquire such capacities, and

-

The nature of the successor regime in

Baghdad, Israel may decide to shift its existential concerns to other

regional threats. Special attention must be directed in this regard to

expanding nuclear trade between Russia and Iran; to Egyptian plans to

build a nuclear power plant near Alexandria, and to recent intelligence

about Libya’s efforts in the nuclear arena. Israel’s decision here will be

contingent to some extent upon precise military outcomes of the American

war on terror.

Preemption

Following the Bush Administration’s

September 20th reaffirmation of anticipatory self-defense and its broadened

emphasis on preemption in the War Against Terror, Israel should now adopt a

similar policy. The Group suggests that such policy pertain to WMD/BN threats,

and that – wherever possible – it be entirely conventional in nature. Preemption

may be overt or covert, and range from “decapitation” to full-scale military

operations. Further, decapitation may apply to both enemy leadership elites

(state and non-state) and to various categories of experts who are essential to

the fashioning of enemy WMD/BN arsenals; e.g., scientists.

The National Security Strategy of the

United States of America stipulates that, “We must be prepared to stop rogue

states and their terrorist clients before they are able to threaten or use

weapons of mass destruction against the United States...” Urging “Proactive,

counter-proliferation efforts to deter and defend against the threat before it

is unleashed”, the document makes clear that America no longer has the only

option to rely on reactive postures. “We cannot,” says the President, “let our

enemies strike first.”

The preemption imperative applies even more

strongly to Israel. More than any other state, Israel’s failure to shift

purposefully to codified counter-proliferation policies could have fully

existential consequences. This shift must be immediate. The Group suggests

strongly and unequivocally that conventional Israeli preemption against selected

enemy nuclear infrastructures now in development be executed as early as

possible, and – wherever possible – in collaboration with the United States.

Where America may be unable or unwilling to act proactively against these

infrastructures, it is essential that Israel be able and willing to act alone.

The Group reminds its readers that

prevention or delay of enemy nuclear deployment would be profoundly different

from preemption of an already-existing enemy BN force. Such issues as time

horizon; target types; operation concurrence; disclosure and certain others must

be analyzed separately for the two contexts. Attempts at preemption against an

enemy that has been allowed to go nuclear may be too risky and may invite an

existential retaliation.

The group distinguishes between two types

of preemptions:

-

Preemption against nuclear

installations capable of eventually producing nuclear weapons, and

-

Preemption in the battlefield (In

most cases before hostilities start).

It is understood that both types of

preemptions be carried out by conventional high precision weapons, not only

because these weapons are more effective than nuclear weapons, but because

preemption with nuclear weapons could be considered as Israeli nuclear first

strikes. If not successful, these strikes could elicit an enemy’s counter-value

second strike with all its existential ramifications.

Tactical Weapons and Other Warfighting Considerations

The Group believes that development of a

nuclear warfighting capacity for Israel (counterforce-targeting) should be

avoided as far as possible. There is no operational need for low-yield nuclear

weapons geared for actual battlefield use. There is no point in spreading (and

raising costs) Israel’s effort on low-yield, tactical nuclear weapons given the

multifaceted asymmetry between Israel and its adversaries.

Overall, the most efficient yield for

Israeli deterrence, counterstrike and deployment purposes is a countervalue-targeted

warhead at a level sufficient to hit the aggressor's principal population

centers and fully compromise that aggressor's national viability.

The Group urges that

Israel make every effort to avoid using nuclear weapons in support of

conventional war operations. These weapons could also create a seamless web of

conventional and nuclear battlefields that Israel should avoid.

The Group opposes the creation of “Red

Lines” concerning use of tactical nuclear weapons. These Red Lines could be

eroded by a political establishment encouraged to use the “easy” nuclear way out

of military dilemma, thus occasioning premature escalation to nuclear war. Red

Lines might also be eroded within the military itself, if IDF elements were to

prompt any unauthorized use of the weapons at their disposal. In our judgment

tactical nuclear weapons and doctrine would increase instability without

offering Israel any real strategic advantage.

Consistent with the basic presumption of

enemy rationality, the Group considers it gainful for Israel to plan for

regime-targeting in certain instances and circumstances. With direct threats

employed against individual enemy leaders and possible others, costs to Israel

(and to the Arab populations oppressed by the targeted regimes) could be very

substantially lower than alternative forms of warfare. Simultaneously, threats

of regime targeting could be even more compelling than threats to destroy enemy

hard targets, but only if the prospective victims were made to feel sufficiently

at risk. We understand that regime-targeting by Israel is unlikely unless a

pattern will first be established by the United States in the expanding War

Against Terror.

The Group offers a final set of suggestions

concerning anticipatory self-defense. Israel must be empowered with a “Long Arm”

to meet its preemption objectives. This means long-range fighter aircraft with

capability to penetrate deep, heavily-defended areas and to survive. It means

air-refueling tankers; communications satellites; surveillance satellites;

long-range UAVs. More generally, it means survivable precision weapons with high

lethality; it also means substantially refined EW and stealth capabilities.

Individually, the need for these assets is already well-known. What is new and

important here in the Group’s suggestion is the recommended configuration of

these assets.

Deterrence

Operational deterrence is essential to

Israeli security in all situations and circumstances. If, for whatever reason,

Israel fails to meet its preemption goals and enemy states acquire nuclear

capacity, it will have to reconceptualize deterrence to conform to the vastly

more dangerous geostrategic context. The Group affirms, again, that Israel’s

primary objective must always be to prevent enemy nuclear weapons in the Middle

East, but if this mission is unrealized it suggests the following: Israel should

immediately end its posture of nuclear ambiguity and take steps toward

purposeful disclosure of its own nuclear assets and doctrine. Such disclosure,

of course, would be limited to those aspects needed to underscore the

survivability and penetration-capability of its nuclear forces and the political

will to launch these forces in retaliation for certain forms of enemy

aggression.

The Group understands that Israel must

always do whatever it can to ensure a secure second-strike nuclear capability

that is recognized by all pertinent enemy states. This means that once nuclear

ambiguity is brought to an end, nuclear disclosure would play a crucial

communicative role. The essence of deterrence lies in the communication of

capacity and will to those who would do Israel great harm. The actual

retaliatory use of nuclear weapons by Israel would signify the failure of

deterrence. Recalling Clausewitz and Sun-Tzu, the very highest form of military

success is achieved when one’s objectives can be met without an actual use of

force.

To meet its “ultimate” deterrence

objectives – that is, to deter the most overwhelmingly destructive enemy

first-strikes, Israel must seek and achieve a visible second-strike capability

to target approximately 15 enemy cities.

Ranges would be to cities in Libya and Iran, and recognizable nuclear bomb

yields would be at a level sufficient to fully compromise the aggressor's

viability as a functioning state. The Group points out that

Israel must also convince all relevant adversaries that it has complete control

over its nuclear forces. The purpose of such

convincing would be to reduce or

remove any adversarial considerations of preemption against Israel.

The Group notes again that where nuclear

targeting is concerned, Israel should focus its resources on counter-value

warheads, targeting between 10 and 20 city assets of crucial importance to the

enemy, but excluding religious assets wherever possible.

Choosing countervalue-targeted warheads in the range of maximum destructiveness, Israel

will achieve the maximum deterrent effect, and will neutralize the overall asymmetry

between the Arabs and the state of Israel. All enemy targets should be selected

with the view that their destruction would promptly force the enemy to cease all

nuclear/biological/chemical exchanges with Israel.

The Group points out that all of its

suggestions regarding nuclear weapons are fully consistent with authoritative

international law. On July 8, 1996, the International Court of Justice at The

Hague handed down its Advisory Opinion on The Legality of the Threat or Use

of Nuclear Weapons (pursuant to request made by the General Assembly of the

United Nations). The final paragraph of the Opinion concludes, inter alia:

The threat or use of nuclear weapons would generally be contrary

to the rules of international law applicable in armed conflict, and in

particular the principles and rules of humanitarian law. However, in view of the

current state of international law, and of the elements of fact at its disposal,

the Court cannot conclude definitively whether the threat or use of nuclear

weapons would be lawful or unlawful in an extreme circumstance of self-defense,

in which the very survival of a State would be at stake.2

The Group maintains that Israel must

display flexibility in its nuclear deterrence posture in order to contend with

future adversarial expansions of nuclear weapon assets. It may become necessary

under certain circumstances that Israel field a full triad of strategic nuclear

forces. For the moment, however, we believe that Israel can manage without

nuclear missile-bearing submarines. This belief holds only as long as it remains

highly improbable that any enemy or combination of enemies could destroy

Israel’s land-based and airborne-based nuclear missiles on a first-strike

attack. The Group recognizes that these circumstances could change in the

future.

To meet its deterrence needs, Israel must

be prepared to:

-

Fully operationalize an efficient,

multi-layered antiballistic missile system to intercept and destroy

a finite number of enemy warheads with the highest possible probability of

success and with a reliable capacity to distinguish between incoming

warheads and decoys.

-

Fully operationalize a robust

second-strike capability, sufficiently hardened and dispersed, and

optimized to inflict a decisive retaliatory salvo against high-value

targets.

-

Continue energetic R&D, service

trials, eventual production/deployment of Boost Phase/Boost Phase Launcher

Intercept systems to add to multi-layered defense.

-

Enhance real-time intelligence

acquisition, interpretation and transmission for instant response.

-

Provide for accurate, real-time

post-strike reconnaissance and assessment.

-

Provide the required C4I system to

handle all above and ground-damage control.

-

Take all necessary measures to

connect the north and south of Israel, bypassing metropolitan Tel Aviv

(roads, railways, gas and oil pipelines, water, electricity, telephones,

etc); and

-

Provide population dispersal for an

early-warned Tel Aviv.

As a rule Israel will do its utmost never

to escalate from the conventional or chemical to the BN. It will do so only as

retaliation against an existential attack/first strike by an enemy. Israeli

nuclear counterforce first strikes (even for preemption purposes) would be

precarious and should be avoided at all costs. For the reasons stated above

Israel should also attempt to have very strong conventional, chemical, and

biological deterrence capabilities. It should not ever be forced to escalate to

the nuclear level for lack of proper response options in lesser capabilities.

Finally, Israel’s deterrence posture must

always be founded upon genuine capabilities. In this connection, the Group

suggests that Israel always avoid any intended gap (IG) between actual and

alleged military capacities. An effort to maintain any IG would be unnecessary

and would likely be unsustainable. Moreover, the consequences of any enemy

discovery of an Israeli IG would be very destabilizing. If, for example, the IG

had been presumed essential to Israeli deterrence, its exposure by an enemy

state or states could provoke overreaction by the enemy. Here, the enemy might

launch an all-out attack upon Israel under the false presumption that other

declared Israeli capabilities were probably fabricated.

From the standpoint of deterrence, there is

a deep and meaningful consistency between actual and alleged capabilities. In

every aspect of nuclear capability, the declared level, by Israel, should be

neither less nor more than the real one. This does not mean, however, that

Israeli declarations need to be very specific. Nor does it mean that merely

having a nuclear force automatically implies having a credible nuclear

deterrence posture. Such a force must always be secure, appropriately

destructive and presumptively capable of penetrating any would-be aggressor’s

active defenses.

Conclusion

A policy paper published by ACPR (Ariel

Center for Policy Research) in March 2002 raised important concerns about

Israel’s deterrent capacities vis-à-vis Iraq or Iran.3

Here, one of our team,

Yoash Tsiddon-Chatto

linked Israeli security to the US War Against Terror (WAT). At the same time,

another member of our group –

Louis René Beres

– urged the creation of a special ad-hoc effort to advise the Prime Minister of

Israel on the growing threat of enemy state and/or terror organization

acquisition of WMD. Professor Beres, who has been the Chair of Project

Daniel, was initially most concerned about Middle Eastern enemy states who might

act as “suicide bombers” writ large; that is, as countries armed with

operational biological and/or nuclear weapons. Such states might be willing in

certain circumstances to accept collective national “martyrdom” in order to

annihilate or bring great destruction to Israel. Although

the Group agrees that such a prospect is conceivable, we have concluded that the

principal existential threats to Israel are still more likely to come from

rational adversaries and that Israel should plan accordingly.

International law is not a suicide pact.

Every state has an established right under international law to protect itself

from enemy acts of aggression. This right is all the more obvious today, when

Weapons of Mass Destruction can inflict existential harms and where aggressors

could calculate, correctly or incorrectly, that they can strike without

incurring unacceptably damaging retaliations.

The United States of America now recognizes

that even the world’s remaining superpower must augment deterrence and defense

options with up-to-date expansions of anticipatory self-defense. Following Bush

Administration codifications of preemption as doctrine, Israel – a country that

is vastly more vulnerable than the United States – should do no less. Seeking,

always, to implement peaceful and diplomatic remedies wherever possible, Israel

must remain fully aware that its adversaries have very different orientations

toward these remedies and that, in certain situations, even threats of

overwhelming retaliatory destruction could fail to deter enemy aggression. What

we are suggesting here is not merely that Israel remain committed to

anticipatory self-defense wherever necessary – after all, such a commitment is

already understood – but that Israel now make fully doctrinal commitments to

conventional forms of preemption in regard to WMD threats. These unambiguous

commitments would be unthreatening and law-enforcing, announcing in advance that

Israel, like the United States, has an inherent right to defend itself without

first absorbing Biological and/or Nuclear aggressions.

American defense policy under President

George W. Bush gathers into one comprehensive whole several interrelated

doctrines for deterrence, defense and preemption. Codified during 2002 in The

National Security Strategy of the United States of America (September 20,

2002) and National Strategy to Combat Weapons of Mass Destruction

(December 11, 2002) this policy offers a coherent doctrine from which specific

tactical and strategic options may be suitably derived and implemented.

Notwithstanding substantial security differences between our two countries, and

the distinct possibility that there will be certain conceptual/operational

errors and failures in America's actual execution of the Bush Doctrine in

particular venues, a similarly institutionalized doctrine could now serve to

enhance Israel's defense posture.

Israel’s strategic future is always a work

in progress. This Report has identified various existential threats to this

future and appropriate policy responses. The Members of Project Daniel stand

ready to offer whatever additional counsel might best serve the security

interests of the State of Israel. With this in mind, we respectfully offer this

Report to the Honorable Ariel Sharon, Prime Minister.

Israel’s Strategic Future

The Final Report of

Project Daniel

Addendum

Israel’s unchanging imperative is to

survive in a very hostile neighborhood. Facing both state and non-state enemies in

the Arab/Islamic world, some of whom remain relentlessly genocidal toward Israel, the

Jewish state must now prepare to systematically harness all resources needed to

endure. Above all, this means constructing the optimal conceptual foundations for national

strategic survival. With this in mind, and with particular attention to the

still-growing dangers of Arab/Islamic nuclearization, the members of Project

Daniel offer Israel’s Strategic Future.

When Project Daniel presented its basic

document to Prime Minister Ariel Sharon on January 16, 2003, Operation Iraqi

Freedom had not yet commenced. Today, in April 2004, the war – in one form or

another – is more than one-year old and (however one might wish to judge the

strategic accomplishments of the conflict) the specific WMD

dangers once associated with Iraq are for now, evidently irrelevant.

Nevertheless, from the standpoint of Israel’s overall strategic doctrine, the

recommendations expressed in Israel’s Strategic Future remain entirely

meaningful and timely. Indeed, conceptually, these recommendations are now more

important than ever before. We refer here especially to the critically enduring

expectations of deterrence, defense, warfighting and preemption doctrine – expectations

carefully discussed in the main body of the Report.

Since the presentation of our original

document, there have been a few relatively minor “victories” in the

indispensable effort to control

WMD proliferation among Israel’s

enemies. The most obvious case in point is Libya. At the same time, the

circumstances in North Korea (which had already participated in a war against

Israel, deploying some Mig-21 squadrons to Egypt in the October 1973 “Yom Kippur

War”), Iran and Pakistan remain highly volatile and dangerous.

At the level of terrorist groups, which are of course sustained by several

Arab/Islamic states, new alignments are being fashioned between various

Palestinian organizations and

al-Qai`dah. The precise

configurations of these alignments are complex and multifaceted, to be sure, but

the net effect for Israel is unmistakably serious.

We, the members of Project Daniel, are

aware as well, that a movement for nuclear “equity” is currently gaining strength

in the Arab/Islamic world and even in parts of Europe. The main argument of this

carefully orchestrated movement is that nonproliferation burdens should be borne

“fairly and equally” by all states in the region, and that Israel cannot be an

exception. If this carefully contrived movement should gather strength and

adherents in the coming months and years, it could place Israel’s nuclear

options in some peril. Without these options, Israel’s genocidal enemies would

quickly understand what classical military thinking has incorporated from Karl

von Clausewitz

(On War), and what was learned long ago by the ancient Greek King Pyrrhus:

There comes a time when mass counts. In this connection

it is important for friends of Israel to understand that our reference to

“genocidal enemies” is altogether literal and precise. Even by the strict

jurisprudential standards defined at the 1948 Convention on the Prevention

and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, the language and actions of

Israel’s state and non-state enemies qualify fully as egregious crimes against

humanity.4

The Arab world is comprised of 22 states

of nearly 5,000,000 square miles and 144,000,000 people. Soon, if Israel is

forced to accede to the idea of a Palestinian state, there will be a 23rd

Arab state, one with particular territorial and tactical advantages in the

accelerating genocidal struggle against Israel. The Islamic world overall

contains 44 states with more than one billion people. These Islamic states

comprise an area that is 672 times the size of Israel. The Jewish state, with a

population of about 5,000,000 Jews – is – together with Judea, Samaria and Gaza

– less than half the size of San Bernardino County in California.

We the authors of Israel’s Strategic

Future have reaffirmed Israel’s long-honored commitment to collective

security and “peaceful settlement of disputes” whenever possible. But it will be

immediately evident to all who consider the United Nations that this world body

has regularly been openly biased against Israel, and that it can never be

counted upon to halt or even impede the genocidal ambitions of Israel’s enemies.

Indeed, at a time when the uniquely barbarous terror of

Hamas

and related Palestinian groups openly defies every constraint of humanitarian

international law (the law of armed conflict is binding upon all combatants,

insurgents as well a states), the UN chooses to condemn not the Arab terror but

Israel’s efforts at counter-terror. In a fashion that seems to resemble the

literary genre of the “Theatre of the Absurd” more than the sober deliberations

of international diplomacy, the Security Council debates Israel’s security

fence, but not the Arab mutilations and murders that make the fence necessary.

Similarly, the world body is quick to condemn Israel’s policy of “targeted

killings” while ignoring the bloody pogroms organized by such

Hamas

leaders as the late Sheikh Ahmed Yassin and the late Abdel Aziz

al-Rantisi.

We might also recall that the UN Security Council, including the United States

of America, voted to condemn Israel’s destruction of Iraq’s Osiraq

nuclear reactor on June 7, 19815 – an expression of anticipatory self-defense6

that was the reason Saddam Hussein did not have nuclear weapons during the 1991

Gulf War or during the past year in Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Israel’s Strategic Future is

founded on the presumption that current threats of war, terrorism and genocide

derive from a very clear “clash of civilizations”, and not merely from narrow geostrategic

differences. Both Israel and the United States are unambiguously in the

cross-hairs of a worldwide Arab/Islamic “Jihad”

that is fundamentally cultural/theological in nature, and that will not concede

an inch to conventional norms of “coexistence” or “peaceful settlement”. This

situation of ongoing danger to “unbelievers” is hardly a pleasing one for

Jerusalem and Washington, but it is one that must now be acknowledged

forthrightly and dealt with intelligently. Moreover, it is a situation that

could combine an eighth century view of the world with 21st century weapons of mass

destruction.

Very early on in our deliberations, the

Group considered a coincident danger; that is, the special strategic risks to

Israel of irrational adversaries (state and non-state) armed with nuclear and/or

biological weapons. Although we concluded that preeminent risks are far more

likely to be associated with fully rational enemies, there may be residual

circumstances in which Israel could be faced with a “suicide bomber in

macrocosm” – enemy state leaders/decision-makers who are actually willing to

absorb overwhelmingly destructive Israeli nuclear reprisals in order to

eliminate the “Zionist cancer”. For this reason, as well as for other specific

circumstances in which Israel’s nuclear deterrent might be eviscerated or

immobilized, we have devoted much of our argument to codification of a credible

and capable preemption doctrine.

We may learn two persistently important

truths from Thucydides’

account of the Peloponnesian War in ancient Greece: (1) that “war is a violent

preceptor,” and (2) that human nature is dreadfully constant. Today, Israel’s

strategic future is poised precariously on a knife’s edge, and the wisdom of Thucydides

can be disregarded only at great peril. It would be a mistake to conclude that

inter-Arab or inter-Islamic dissension at any level, including open warfare,

would substantially reduce risks of violence to Israel, or that Israel can

presently draw any true measure of security from formal peace agreements with

its enemies. Ultimately, President Bush is correct in his view that Arab/Islamic

democratization is necessarily antecedent to regional peace, but it is just as

apparent that this remedy is still many years away. In the interim, therefore,

both Israel and the United States must maintain steady momentum in their War

Against Terror (WAT)

and in the absolutely imperative control (including, if necessary, appropriate

preemptions) of nuclear proliferation. Building upon the solid foundations of

Libya’s recent nuclear renunciation, attention must now be directed especially

to scale down the nuclear programs not only of Iran, but also of Algeria and

even Egypt.

As a “violent preceptor”, Operation

Iraqi Freedom yields several important lessons. In its initial combat phases,

“Gulf War II” has been a war of high-precision ordnance, in contrast to

Operation Desert Storm, which had been a “war of platforms”. The overwhelming

majority of bombs and missiles fired in Operation Iraqi Freedom were accurate

enough to permit about 600 strike aircraft – deployed farther away from their

targets than in Operation Desert Storm – to achieve primary offensive objectives

in some 24 days. From the standpoint of these objectives, it follows that what

“counts” in such offensive operations is not missions per se, but rather

number of ordnance per target hit or destroyed.7

Nonetheless, even where this “lesson” has been learned by Israel and the United

States, it must remain obvious that an initial offensive operational victory in

wars against rogue regimes and corollary wars against terror is only the

beginning of much wider forms of struggle.

In the main body of our Final Report, we

note a recommended “Paradigm Shift”, and identify associated changes to Israel’s

defense expenditures. Optimally, a satisfactory level of conventional

deterrence/war-winning capacity can be maintained by Israel without substantial

budgetary expansions. By definition, this would require a reduction in

weapon-carrying platforms (e.g., tanks, aircraft) and a corresponding reduction

in manpower, training and maintenance costs without diminishing the desired

level of overall combat effectiveness.

In essence, the budgeted paradigm-shift

must allow the IDF

to maintain a needed level of potential number of targets destroyed over

a pertinent span of time – a goal that will require sophisticated, “intelligent”

weapons; lighter, more lethal, with longer-ranges and – very importantly –

possessing precise day/night, independent (fire and forget) unjammable

guidance systems.8 The recommended paradigm shift will also require additional

deterrence/war-winning capabilities in both the Terror and WMD

sectors. Although there is a certain overlap of operational requirements between

sectors, the slightly-reduced

budget allocations for

conventional deterrence will not suffice to sustain the vastly-increased needs

for anti-terror and (especially) WMD-warfare

requirements.

The authors of this

report wish to highlight several areas where Israel’s conventional defense

posture is being negatively impacted by recent budget cuts.

The first of these is

in the area of research and development.9 Israel’s FY 2004 defense budget

eliminates a substantial part of the funding for new R&D initiatives as a direct consequence of an

overall cut of NIS 3 billion (US$680 million) in military expenditure.

Innovation in weapons technology is the lifeblood of the country’s military

establishment and has been responsible for ensuring that its armed forces can

prevail over any combination of numerically superior enemy states. It also is

the engine for the country’s high technology economy. Reducing

investment in new military technology leaves Israel vulnerable to its enemies

who are acquiring new and improved weapons systems at a prodigious rate.

A second concern is

the inadequate funding being allocated by Israel to military Operation and

Maintenance (O&M) accounts. It is these accounts that pay for day-to-day

necessities from pay and allowances to training and base support. The three-year

old Palestinian war has forced the IDF to divert funds from its regular O&M to

pay for ongoing operations in the territories. The war on terrorism and the

security barrier have drained away additional resources. Owing to the growing

shortage of O&M funds, troop training has been reduced across the board to

include flying hours for the Air Force, steaming hours for the Navy and maneuver

hours for IDF land forces.

Third,

with rare exception, Israel’s military leaders are being forced to cut back on

the acquisition of new, state-of-the-art war fighting platforms.

Conventional military

strength is composed of many factors. Those mentioned above are just a few of

the indicators that point to a disturbing trend among Israel’s armed forces, one

that if allowed to continue could seriously erode the country’s sustained combat

capability as well as its ability to deter non-nuclear aggression. The

maintenance of a strong, seamless conventional defense posture is key to being

able to deter aggression along the entire threat continuum. Israel’s military