The tank has long been a staple of combat

in the Middle East. It featured prominently in the North African campaign of

World War II and in every major clash between Israel and its Arab neighbors

since the Jewish state declared its independence in 1948.

Even today, it is the heavily armored main

battle tank (MBT) that stands watch along Israel’s border with Lebanon and is

the first line of support for infantry patrolling the Palestinian territories.

Across the Arab World, the tank remains central to war fighting doctrine and the

weapon of choice for commanders wishing to seize and hold ground in virtually

all battlefield conditions.

Yet despite this record of distinguished

service, there are those in the military community who contend that the era of

the tank is rapidly fading. They point to dramatic advances in anti-tank guided

missiles (ATGMs), improvised explosive devices (IEDs), anti-armor mines,

refinements in close air support and the proliferation of unmanned vehicles as

evidence that a global revolution in ground combat is now underway.

For many, this means a gradual move away

from the large and expensive weapons platforms that have long dominated modern

warfare and towards more nimble, less expensive fighting vehicles. What these

new systems lack in firepower and protection their designers insist is made up

for in stealth, range and operational flexibility.

Even in Great Britain, home of world’s

first tanks, the Ministry of Defence (MoD) is now reevaluating the place of

tanks in the Army’s order of battle. With budget cuts looming, the MoD is

shifting its focus away from traditional armored platforms and towards an array

of multi-role weapons, rapidly deployed forces and improved surveillance

systems. According to a recently released White Paper, this could mean the

elimination of two armored regiments and nearly one third of the country’s heavy

armored force, approximately 120 Challenger 2 tanks, over the next several

years.1

The lessons now being learned by Coalition

forces in Afghanistan and Iraq will have a significant influence over the way in

which military planners assess the future role of the tank. In both wars, heavy

armor played a critical role in the initial days of fighting. But as Coalition

operations shifted to a policing function, the tank’s use as an instrument of

urban pacification and civil control diminished. This changed in the Spring of

2004 when major fighting erupted again across Iraq’s Sunni triangle in places

like Fallujah and ar-Ramadi. Commanders then quickly abandoned their lighter,

less secure assault vehicles and turned once again to the heavy tank for

protection.2

As technology permits greater lethality to

be packaged into ever smaller man-portable systems, the vulnerability of heavy

armor unquestionably has increased. Even so, one fundamental truth regarding

defense on the battlefield remains unchanged – more is better. In this new and

deadlier age of asymmetric warfare, adaptation and technological innovation are

the keys to the tank’s survival. But it is funding, in ever larger amounts, that

will make this evolution possible.

In the race for the high ground the

venerable tank could well be one of the first casualties of the modern

battlefield or its greatest singular achievement. Most assuredly, it will be in

the sands and cities of the Middle East where that judgment will be made.

Modernizing Arab Armor

While some Western military strategists may

be predicting the demise of the tank, there is little sign that this prophecy

has taken hold in the Arab World. For over a decade, countries like Egypt, Saudi

Arabia, Kuwait, and Jordan have worked vigorously to modernize their heavy

armored fleets. They have spent billions of dollars acquiring new,

state-of-the-art platforms from the foremost tank manufacturers in America and

Europe and billions more upgrading their old Soviet equipment with Western

technology.

Corresponding improvements in training,

maintenance, command and control and air-land battle tactics have given the

armored forces of the Arab World a potency they lacked in the past. This is

particularly true for Egypt which has significantly improved both the lethality

and survivability of its tank force. After many years in the technological

wilderness, Egyptian armor is once again emerging as a powerful threat to

Israel’s security.

Today, the Jewish state finds itself

outnumbered 2.3 to 1.0 in the number of heavy tanks fielded by Its Arab

neighbors. In 2003, Arab tank inventories grew to new levels with the following

countries leading the way: Syria: 3,700, Egypt: 3,000, Jordan: 990, Saudi

Arabia: 750 and Lebanon: 280.

In any future ground war, Israel’s arsenal

of approximately 3,900 tanks must contend with a combined Arab force of 8,720

tanks. While many of these consist of older Russian T-72, T-62 and T-55 models

found principally in the Syrian arsenal, the region’s governments are moving to

replace these vehicles with newer systems. Damascus, for instance, is upgrading

to the newer Russian T-80 tank.

The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan has

embarked upon a program to expand its fleet of 288 British-made Challenger-1

tanks by an additional 100 vehicles. The turrets will be retrofitted with the

L11 medium-pressure 120mm smooth bore gun manufactured by RUAG Land Systems of

Switzerland.3 This new gun will give the

Al-Hussein, as the Challenger-1 is known in Jordan, the ability to fire depleted

uranium (DU) ammunition. This modification will enhance significantly the

firepower of the Challenger-1, giving the Kingdom’s tank force an accuracy,

reach and lethality it has lacked up until now.

Changes are coming as well to the Kingdom’s

fleet of American M60 tanks. In a three-way partnership between the Raytheon

Technical Services Company LLC (RTSC), RUAG and the King Abdullah Design and

Development Bureau (KADDB), Jordan will

upgrade100 M60 A1 and A3 MBTs with the Phoenix Level 1 Integrated Fire Control

System (IFCS).

According to RUAG, the IFCS will provide

the tanks with “second generation FLIR imaging, eyesafe laser ranging and

digital ballistic computing in a stabilized and synchronized cannon and sight

system”.4 The tanks also will gain the ability

to fire while in motion. An upgrade from the 105mm to the 120mm Compact Tank Gun

(CTG) will make Jordan’s M60s compatible with the NATO standard.

A final contract awarded by the Kingdom of

Jordan to Raytheon in April, 2004, for $64.8 million will complete the upgrade

of the entire Jordanian M60 fleet to the IFCS configuration. According to the

Raytheon announcement, “this upgrade improves the M60s firepower capability and

survivability by offering a significant improvement in first-round hit

capability” and “true shoot-on-the-move capability”.5

The Kingdom of

Saudi Arabia may follow Jordan’s lead in upgrading its own M60A3 tanks to the

Phoenix configuration. This would include not only replacing the current 105mm.

gun with a RUAG 120mm. smoothbore model, but enhancing the tank’s armor

protection as well.

According to

recent reports, Saudi officials are now in discussions with Jordan’s KADDB over

the possibility of incorporating the IFCS into its M-60 tanks. Also under

consideration is an engine upgrade to the General Dynamics 950 HP AVDS

1790-6. This would increase the effective range and overall performance of the

Saudi M-60 tanks while also enabling them to accommodate the increased weight of a

new gun turret. Currently, the Royal Saudi Land Forces operate approximately 150

M-60 A3 tanks in the TTS configuration along with 315 M1A2 Abrams tanks.6

Though not an Arab country, the Islamic

Republic of Iran fields an armored force of approximately 1,500 tanks. Israeli

military planners are keenly aware that this force could one day find itself

fighting alongside Arab armies in a confrontation with the Jewish state.

In a move that could signal the emergence

of a new political realignment in the Middle East, Iran and Egypt opened up a

strategic dialog at the end of 2003. The meeting between the country’s two

presidents was the first since Tehran broke off relations with Cairo following

the signing of its 1979 peace treaty with Israel.

Since coming to power this same year,

Iran’s religious leaders have been among the most strident opponents of both

American and Israeli influence in the region. Tehran maintains a close alliance

with Syria and along with Damascus is a principal arms supplier to the Hizbullah

guerilla movement battling Israel from bases inside of Lebanon.

In the 1990s Iran joined Israel and Egypt

as one of only three countries in the Middle East capable of producing its own

armored vehicle. While the Zolfaqar light tank is no match for Israeli

anti-armor weaponry, it does add to the numerical advantage in armor already

enjoyed by Jerusalem’s adversaries. The tank incorporates a laser-guided

targeting system and is reputed to be “lighter and more maneuverable” than

earlier models.7

When planning the country’s future defense

requirements, Israeli military planners must consider the full range of

capabilities that could be amassed against the Jewish state.

For Israel, though, the real danger lies in

pace of the Iranian military build-up in recent years and their increasing

ability to weaponize and deliver unconventional arms. According recent

estimates, between 2000 and 2001 Teheran increased its defense budget by upwards

of 50%.8 In addition to the acquisition of a

broad range of modern battlefield systems, Iran appears also to be seeking a

first strike nuclear capability that could soon be directed against Israel.

Military observers believe that Iran already has substantial stocks of chemical

and biological weapons at its disposal.

What Iran lacks in

offensive armor capability is offset, in part, by its growing ability to

neutralize its opponents land systems through the first use of unconventional

weapons.

The Growing Egyptian Threat

With a fielded force of 420,000 soldiers,

Egypt has one of the largest and most professional standing armies in the Middle

East. Equipped with some of the region’s most modern weaponry, it also poses the

greatest conventional threat to Israel of any Arab state. This danger continues to grow as Cairo pursues an ambitious program of rearmament

unprecedented in its recent history. Heavy Armor and systems to defeat heavy

armor are key components of Egypt’s new offensive military posture.

The centerpiece of Egypt’s armored force is

the American-made M1-A1 main battle tank. Cairo began integrating the M1 Abrams

into its military strategy in 1988 following the construction of Tank Assembly

Plant 200 in Helwan just outside of Cairo. At a cost of about $1 billion, this

plant was paid for largely with US foreign assistance dollars.

The M1 is produced in Egypt under a

licensed co-production agreement with General

Dynamics Land Systems (GDLS). About 60% of each Egyptian M1 is manufactured by

GDLS at plants in the US. The components then are shipped to Egypt in kits for

final assembly and testing. The remaining 40% of each vehicle is produced

locally in Egypt.

In a little over a decade, the Helwan tank

plant has spawned a vast network of local factories that now are capable of

fabricating many of the parts needed for the repair and maintenance of the

country’s armored fleet. This has dramatically improved the Army’s field

readiness while strengthening Egypt’s overall military production base. The

country’s National Organization for Military Production now oversees 16

industrial sites.9

Following the production of the first 555

tanks begun in 1991, Cairo authorized additional orders. The latest of these

came in October 2003, with the approval by the Pentagon of 125 M1A1 tank kits

for $920 million. A full spare parts and training package also was included in

the deal.10 This brings to 880 the number of

Abrams American tanks now in the Egyptian arsenal.

Plans call for a total of 1,500 M1s to be

produced and fielded with the Egyptian Army. Eventually, the country hopes to

replace its entire inventory of Soviet-era tanks. In the meantime, the Army is

studying the possibility of upgrading its 600 T-62 tanks with a new, more

powerful engine. Favored at this time is the 1,500hp SACM V8X-1500 Hyperbar

diesel engine used in the French Leclerc tank.11

Egypt’s 800 T-55 tanks remain in storage.

An American-Fueled Arms Race

Eager to solidify its position as the

number one arms supplier to the Middle East, Washington has shown little

reluctance to hold back on the transfer of advanced equipment to the region.

Egypt has been one of the largest purchasers in recent years with the

acquisition of a vast assortment of missiles, combat ships, artillery, attack

and reconnaissance aircraft, surveillance drones and munitions. Tanks are no

exception.

In a surprise move, the Defense Department

announced in late 2003 that it would permit the M1A1 tank fleets of its allies

in the Middle East to be upgraded to the M1A2 configuration. The move would

dramatically enhance both the lethality and survivability of the Abrams by

giving it capabilities comparable to front line US forces. The only other

countries in the Middle East that currently operate M1A2 tanks are Kuwait with

218 and Saudi Arabia with 315. Recently, Washington approved a $26 million

contract from General Dynamics Land Systems to reconfigure the first 14

Egyptian Abrams tanks to the M1A2 model.12

So effective was the M1 during the 1991

Desert Storm campaign that not a single round fired by a Soviet-made T-72 was

able to penetrate its armor plate made of depleted uranium. In fact, most Iraqi

tanks were engaged by US forces beyond their firing range and destroyed by M1

tanks at between 3,000 and 3,500 meters using M829A1 APFSDS-T ammunition.

The M1A2 upgrade is an attractive option

for Egypt which is eager to narrow its technology gap with Israel. Nearly a

quarter of a century after the peace treaty between Egypt and Israel was signed,

Cairo still nurtures the goal of achieving strategic parity with the Jewish

state. Egypt’s Chief of the General Staff, Marshal Hussein Tantawi, has made it

plain that his country not only seeks to improve the effectiveness of its air,

land and sea forces, but is working to give them a power projection capability

as well.

In August, 2001, just one month before the

terrorist attacks on New York and Washington, a senior

Egyptian official was

reported to have threatened that if Israel reoccupied the Palestinian

territories, Egypt order armored units belong to its Third Army into the Sinai

Peninsula.13

Talk of this sort has done little to slow

the transfer of American arms to Egypt. In fact, the pace has quickened in

recent years as Washington has emerged as the preferred arms supplier to the

Middle East, a region already bristling with armament and conflicts on nearly

every border.

Understandably, policymakers in Jerusalem

have become increasingly worried that the US is abandoning its historic

commitment to ensure Israel’s qualitative military edge against any combination

of adversaries. It is a pledge that has been reaffirmed by successive

administrations, both Republican and Democrat, over the last two decades.

Instead of strengthening Israel, this proliferation spiral has only weakened the

country, draining its already fragile economy of scare resources and forcing its

military to devise new and evermore imaginative battlefield solutions to weapons

supplied by Israel’s principal ally.

Jerusalem’s concerns were reinforced in

February 2002, with the declaration from Cairo that Egypt no longer considered

its defense relations with Washington connected to its peace treaty with Israel.14

Instead of issuing a strong condemnation of this policy shift, the Bush

Administration rewarded Cairo by agreeing to the sale of 53 satellite-guided

Harpoon Block II anti-shipping missiles to Egypt. This advanced system can be

employed like a cruise missile to accurately strike targets on both land and

sea.

Responding to Egypt’s massive arms build-up

Israel’s Defense Minister, Shaul Mofaz, told the Israeli daily Ma’ariv

recently:

We look with concern at the

strengthening of Egypt and we ask: what is it for? After all, we have peace with

Egypt and I see no country threatening them. A new reality may develop that in a

few years there will be a different leadership in Egypt and that could change

how they relate to Israel.15

In fact, the situation today in Egypt looks

very much like it did in Iran during the last days of the Shah. The country’s

growing political instability, lack of a clear succession plan and the growing

power of radical Islam, could easily throw the country into chaos. The result

would be that a large amount of highly sophisticated weaponry would fall

suddenly into the hands of individuals committed to the downfall of Israel and

the destruction of US interests in the Middle East.

Since 1981, Washington has contributed

significantly to the operational effectiveness of the Egyptian armed forces by

sponsoring the biannual Bright Star exercise. Armor and anti-armor scenarios

have always figured prominently in the training regime. In recent years, the

aggressor force used in the exercises has been modeled after the Iraqi military.

During the last Bright Star gathering 58,000 troops from the US, France, Britain

and several Gulf States converged on Egypt for a month of war games and

information sharing.

Ironically, this activity has allowed the

Egyptian armed forces to refine their operation doctrine and in fact to benefit,

indirectly, from many of the hard won lessons learned by Israel in its various

military campaigns. While Israel and the US maintain a close working

relationship at all levels of military interaction, the fact remains that

Jerusalem can not control what American officials do with the observations and

insights they glean during joint exercises with the IDF.

One of the most outspoken Israeli critics

of the Egyptian military build-up has been Yuval Steinitz, chairman of the

Knesset Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee. In a recent report he noted:

The last decade has seen a very sharp rise in

military expenditures in Egypt, beyond the amounts that poor country gets from

the United States annually… Up to now, Egypt has received more than $30 billion

in military aid from the United States. Israel has received slightly more in the

last 22 years, but we have had to spend much of it on war – against Palestinian

terrorism, against Hizbullah in the north, against the Iraqis who in 1991 struck

Israel with Scud missiles, and other military campaigns Israel was forced to

conduct.16

It is in the area of armored systems and

the equipment needed to support offensive armor operations where the US has been

particularly helpful to the Egyptians. In 2003, Washington agreed to sell Egypt

10,040 non-standard

Armor Piercing Fin

Stabilized Discarding Sabot-Tracer Kinetic Energy Tungsten Advanced

(APFSDS-T) armor-piercing rounds under a contract worth $54

million.17 This advanced tungsten projectile,

used in conjunction with the improved targeting systems in the M1A2,

significantly enhances the killing power of the American-made tank.

In 2002 Egypt purchased 5,000 KEW-A1 armor

piercing shells from the US made of depleted-uranium (DU), the tank ammunition

adds significantly to the lethality of Egyptian armor.18

Another contract awarded to Alliant Techsystems in August of that year called

for assisting Egypt to establish an indigenous capability to produce 120 mm tank

training ammunition.

Recently, Egypt has made a number of

additional acquisitions which directly support the modernization of Cairo’s

armored fleet as well as its anti-armor capability. By supplying this equipment

and training the US has enabled Egypt to field a military force tailored to

offensive operations. Some of these systems include:

-

Co-Production of 21 M88A2 Hercules Heavy

Recovery Vehicle Kits. These vehicles are used for “towing, wrecking, and

hoisting operations supporting recovery operations and evacuation of heavy

tanks and other tracked combat vehicles”.19

-

Purchase of “26 Extended Range-Multiple

Launch Rocket Systems (ER-MLRS) with fire control panels, 485 ER-MLRS rocket

posts (six rockets per pod), 22 reduced range practice rocket posts (six

rockets per pod), one MLRS fire control proficiency trainer, three M88A2

recovery vehicles, 30 M577A2 command post carriers…” and other support

equipment.20

-

Purchase of 459 AGM-114K3 Hellfire II

Air-to-Surface Anti-Armor Missiles.

-

Purchase of 500 M1045A2 High Mobility

Multi-purpose Wheeled Vehicles (HMMWV) to be fielded with TOW weapons systems.21

-

Approved the delivery of 120 embedded

diagnostics personality system vehicle sets for the M1A1.22

-

Purchase of components for

surface-to-surface rockets, principally M77 grenades with new fuses.23

As the weight of Arab arms tips ever more

precariously against Israel, Washington continues to deny it is a large part of

the problem. In each of the notifications it sends to Congress of pending arms

sales the Pentagon trumpets the same well worn assertion, that:

“The proposed sale of this

equipment and support will not affect the basic military balance in the region.”24

The facts, though, suggest otherwise.

Indeed, the Pentagon has never provided a

means for accurately gauging just how the sale of offensive weapons to Arab

allies not under threat of attack will help to preserve the balance of power in

the region.

The US Department of Defense justified its

recent sale of an additional 125 M1A1 tanks to Egypt by declaring:

This proposed sale will

contribute to the foreign policy and national security of the United States

by helping to improve the security of a

friendly country which has been and continues to be an important force for

political stability and economic progress in the Middle East.25

The use of such

boilerplate language in virtually every congressional notification makes a

mockery of a process which is supposed to provide oversight and direction to

American arms sales policy.

Many political observers find it

astonishing that Washington continues to lavish military hardware on Egypt

despite the country’s increasingly confrontational stance towards the US. In

recent years the two governments have sharply divided over questions of Iraq

sanctions, the Bush Administration’s toppling of the Saddam Hussein regime and

the subsequent US occupation of Iraq, Washington’s support for Israel, America’s

post-9/11 policy of pre-emption and the White House goal of extending democracy

throughout the Middle East.

Four AGM-114

Hellfire Missiles Mounted

on a Wing Pylon of an AH-64 Apache Helicopter

Source: US Army

TOW System Mounted on an HMMWV

Source: Thiokol

Multiple Launch

Rocket System (MLRS)

Source: Redstone Arsenal

Despite this divergence in policy, Egypt’s

President, Hosni Mubarak, continues to tout his nation as one of America’s

closest allies in the region. That show of fealty has brought enormous financial

rewards. In addition to the $1.3 billion in military assistance Cairo receives

annually from the US, the Bush Administration approved an additional $300

million in aid in 2003 along with $2 billion in loan guarantees, ostensibly to

offset the loss in trade revenue resulting from the Iraq war – a war which Egypt

opposed.

Congress, though, has been less than

sanguine about Egypt’s treatment of the US and Israel in recent years. In

January 2004, Representative Anthony Weiner (D-NY), introduced a bill that would

convert US military assistance to Egypt into economic assistance as a protest

against that country’s growing militancy.

Termed the “Egyptian Counterterrorism

and Political Reform Act”, the bill makes note of Egypt’s failure to halt the

smuggling of weapons contraband across its border with Israeli-controlled Gaza,

its public support of Hizbullah attacks against Israel, the continued incitement

against the US and Israel in the government controlled press, Cairo’s flagrant

abuse of human rights and its refusal to normalize relations with Israel despite

commitments made in the 1979 peace treaty between the two countries.26

In a similar vein, Senator Mitch McConnell

(R-KY),

Chairman of the US Senate Foreign Operations Appropriations subcommittee has

called for the wholesale reform of Egyptian economic and military programs as

well as a halt to its human rights abuses as a pre-condition of future American

assistance.27

In the autumn of 2002, with war against

Saddam just months away, Washington asked the Mubarak Government for

permission to allow American forces access to Egyptian bases.28 Mubarak refused. Yet, just over a year later, Washington agreed to a strategic

dialogue with Cairo aimed at improving US-Egyptian defense ties and bolstering

Egyptian defenses.29

In October, 2002, Egypt conducted the

latest in a series of large scale live-fire exercise in the Sinai Peninsula

designed to test the inter-operability of its modernized air defense capability.30

The 10 day exercise termed “A`asar-2002”, focused on the breakout of the Third

Army across the Suez Canal and through fortifications. According to reports 120

aircraft participated in the exercise which used “reconnaissance and imaging

technology to destroy mock enemy targets”.31

Tanks and armored vehicles were among the targets. Israel, the country with whom

Egypt has a peace treaty, was the presumed adversary.

In recent years, Egypt also has stepped up

its consultations with Syria,32 China, North

Korea and Russia in a bid to boost military cooperation and diversify its

sources of arms.33 The result is an arsenal

bristling with weapons of a clearly offensive character. Among the most

worrisome are 24 No-Dong missiles provided by North Korea. Each can be modified

to carry a nuclear, chemical or biological warhead and has an enhanced range

capable of covering all of neighboring Israel.34

In 1996 Egyptian Chief of Staff

Tantawi declared:

Peace does not mean

relaxation. The endless development of military systems and the arms race

prove that survival is only assured by the strongest and that military

strength will always be necessary. Military strength has grown to be a

prerequisite of peace. Any threat to any Arab or African country is a threat

to Egypt’s national security.35

Enter the Merkava

Israel’s answer to these improvements in

Arab armor is the Merkava main battle tank. First deployed in the late 1970s,

the Merkava, or “Chariot”, is Israel’s only domestically built heavily armored

combat system.

Today, the Merkava forms the backbone of

the Israeli armored fleet with nearly 1,300 vehicles in active service. Its

rugged yet flexible design makes it ideally suited to force-on-force engagements

or use in providing tactical support to Israeli soldiers during times of civil

unrest.36 Eventually, the IDF plans to replace

the country’s entire inventory of aging American-made M-60 (Magach) tanks with

the Merkava.

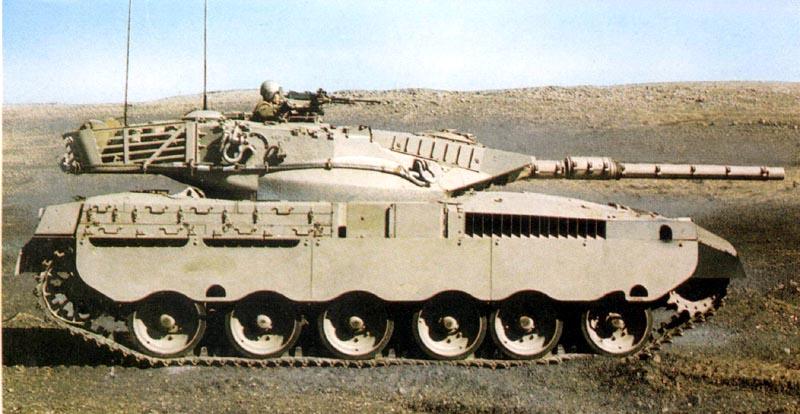

Israel's Magach 7A

Tank; a Variant of the US M60

Source: Daniel Machacek, 2001

The Merkava has undergone four major design

changes since its introduction into the country’s order of battle. In its most

modern configuration, the Merkava Mk 4 was introduced into the IDF in the

summer of 2003. The tank boasts a stabilized gun platform, advanced suspension,

a high velocity smoothbore 120mm gun, full night fighting capability, individual

air conditioning, a state-of-the-art fire control system, a 10 round

electrically operated magazine, and an upgraded GD883 V-12 engine rated at 1,500

hp.

The main gun can fire an array of

ammunition to include 120mm kinetic, HEAT and anti-personnel rounds as well as

the Israeli-developed Lahat, a tandem warhead missile designed to defeat armored

vehicles shielded with reactive armor.

In the view of many of the world’s armor

experts, the 65 ton Merkava is equal to, or better, than any of its rivals. It

also is considered to be among the “best protected tanks in the world”.37

Its advanced modular armor system protects the vehicle against the “penetration

of APFSDS (Armor Piercing Fin Stabilized Discarding Sabot) shells and all known ATGMs”. Extra plating shields the turret from top-down attack.38

So confident is the IDF in the

survivability of the Merkava that it has indicated a willingness to retire two

of its older armored vehicles for every Merkava tank it procures.

The Merkava is the brainchild of Israel’s

legendary tank designer, General Israel Tal, who not only sought a highly

maneuverable multi-role armored vehicle, but also one which placed a premium on

crew survivability. For added protection, the vehicle’s

engine is mounted forward of the crew compartment

while its ammunition is stored towards the rear for better protection.

Merkava MK1. First Production Model.

The tank first saw battle during the 1982 Peace for Galilee Operation.

Source: Israel Defense Forces

Unlike other main battle tanks, the Merkava

doubles as a troop transporter. Its rear entry design enables up to eight fully

equipped soldiers to be carried safely into combat. A 60 mm mortar mounted

inside its hull along with three 7.62 mm machine guns permits the crew to

provide suppressive fire at close range while also using its main gun to deliver

precision strikes against fortified enemy positions.39

This was proven in April 2002, during

Operation Defensive Shield when the IDF employed Merkava tanks to dislodge

Palestinian terrorists holed up in the fortified concrete buildings in the Jenin

refugee camp.40 The Merkava was the weapon of

choice for military commanders concerned that the use of F-16 aircraft and

artillery to destroy terrorist positions would risk unacceptable collateral

damage and lead to a high loss of civilian life within the densely packed

refugee camp.41 Since the collapse of the Oslo

process in September 2000, the Merkava has successfully supported Israeli

military operations throughout the West Bank and Gaza.

Even as the Merkava has significantly

bolstered Israel’s security, the presence of large numbers of the American M1

Abrams tanks in the hands of a well-trained enemy could alter the strategic

equation in the region. Used in conjunction with advancing artillery, close air

support and missiles armed with chemical

or biological warheads, the M1 could

present the IDF with a situation it has never before faced – near parity in

offensive armored systems.

To address this challenge, the Merkava

incorporates the Amcoram LWS-2 laser warning system that allows a commander to

detect and track the launch of incoming missiles. Its survivability is further

enhanced by the incorporation of a positive pressure crew cabin to protect

against an external NBC threat. Four cameras mounted in hardened recesses on the

hull afford the commander a 360 degree panoramic view of the tank’s surroundings

under both day and night conditions.

The Merkava is the centerpiece of Israel’s

three regular and nine armored divisions. It is the principal instrument through

which IDF ground commanders are able to implement Israel’s version of lightening

war, a doctrine which calls for the IDF to win all of its battles quickly and

decisively and with the fewest possible casualties.42

When fully mobilized, Israel is able to increase its armored strength from 20 to

33 brigades enabling the country to simultaneously defend against ground attack

along each of its borders.

Targeting for the Merkava’s main gun is

carried out by a ballistics computer and aided by an advanced forward looking

infrared (FLIR) system. Developed by El-Op, it can operate under all weather and

light conditions.

The debate over the Merkava has its

corollary in the recent decision of the IDF to acquire the American-made Stryker

LAV-3, a lightly armored personnel carrier (APC) that is to replace its older

M-113A1 and M-113A2 APCs. Weighing in at 19 tons and with a maximum speed of 62

mph, the Stryker sacrifices lethality and protection for speed. It operates on

eight

wheels instead of tracks and can travel for miles even when all of its tires are

flat.

Following the lead of the US Army, the IDF

sought a combat transport vehicle that could deliver soldiers to the battle

front with greater maneuverability than current APCs while also being able to

operate in the crowded urban terrain of the West Bank. The IDF plans to buy 500 Strykers for $750 million.43

Stryker: US Army's

Interim Combat Vehicle

Source: US Army

Stryker in Iraq,

Retrofitted with "Slat" Armor

for Added Protection against RPGs

Source: Free Republic

Proponents of heavy armor note that the

Merkava is optimized for just these conditions while also having the ability to

insert troops into hostile environments under the safest and most comfortable

conditions possible. In past years, the IDF had rejected the Bradley Fighting

Vehicle (BFV), another lightly armed combat system, in large part because it

lacked sufficient armored protection.44

Unlike the Merkava, the Stryker lacks

a powerful gun, is vulnerable to RPGs and IEDs and has no air conditioning, an

important consideration when desert temperatures can often soar above 110

degrees in the vehicle. Its skin is composed of steel and aluminum and is covered

with 130 protective tiles. The US first deployed a Stryker brigade to Iraq in

October, 2003. Two months later, on December 14th, the Stryker’s

vulnerability was demonstrated when an IED destroyed one vehicle in an attack

near Ar-Ramadi.

The IDF is anxiously monitoring the

Stryker’s performance in Iraq knowing that its success or failure will be

influential in the debate over what type of armored force will be most useful

for Israel in the years to come.

Challenges Facing Israel

While the Merkava represents the pinnacle

of heavy armor systems, its future as an ongoing industrial concern remains in

doubt. Faced with the effects of a deep recession, a severe drop in government

revenue and the rising cost of the Palestinian war, advisors to Israel’s Prime

Minister, Ariel Sharon, have argued that the program has simply become

unaffordable and must be scrapped.

Israel's Merkava MK4 Main Battle Tank

Source: Israeli-Weapons.com

The first hint of trouble came during the

summer of 2003 as Israel’s Ministry of Finance was preparing its FY 2004 budget

proposal. At that time the Treasury recommended a reduction in defense

expenditure of approximately NIS 7.1 billon or $1.6 billion. The Ministry of

Defense countered that a decrease of this magnitude would break the back of the

IDF by forcing the cancellation of critical programs and hasten the drastic

cutback in the Army’s operational tempo at a time of national emergency.

Israel’s General Staff argued that even a reduction of NIS 3 billion ($684

million) was unacceptable.

With little room to maneuver, officials at

the Finance Ministry, supported by those in the IDF Planning Branch, proposed

halting the manufacture of the Merkava tank as a way of slowing the country’s budgetary

hemorrhage. Their recommendation reflected a growing split within the ranks of

the military over whether the growing lethality of modern anti-tank weapons was

in fact making heavy armored vehicles obsolete.

By one estimate, eliminating the Merkava

program would save the IDF less than NIS $1 billion annually, roughly $220

million, or about the amount spent each year on the acquisition of 50 tanks.

The effect on the Israeli economy as a

whole would be far more significant with the cost in unemployment, missed

investment, lost exports, and curtailed research and development reaching,

perhaps, into the billions of dollars. Indeed, the

negative economic effects could well exceed those of the cancelled Lavi fighter

program nearly two decades ago.

Defense is one of the principal engines of

the modern Israeli economy and military R&D is often the catalyst for innovation

in the civilian sector. Products derived from defense research form the basis

for much of the country’s high technology exports. Without the Merkava, the

industrial base will lose an important infusion of technical know-how and

investment.

In yet, another sign of growing military

austerity, the Israeli MoD has eliminated funding for all new R&D projects in

its FY 2004 defense budget. This is a direct

result of a cut in overall military

expenditure of NIS 3 billion (US$680 million).45

Speaking at the Herzliya Conference in

December 2003, Yaakov Sheinin, CEO of

Economic Models Israel

noted the

enormous impact of defense on the Israeli economy.

Every dollar in Ministry of Defense orders

produces $2.40 in defense exports, which have an added value of 66%. If the

economy emerges from the recession with five percent growth in 2004, it will

take until 2010 before employment falls to six percent. For every public sector

worker they want to fire, the private sector wants to fire two.46

Critics of the plan to scuttle the Merkava

have been quick to rally in support of its continued production. Former Defense

Minister, Moshe Arens observed:

Developing a new fighter aircraft at this time

will take more resources than Israel could possibly afford. It might be done if

another partner could be found for the project. As for the Merkava,

it is the best main battle tank in the world and its production should certainly

not be stopped.47

According to the Israel Manufacturers

Association (IMA), the Merkava program is responsible for between $200 million

and $250 million in annual defense technology exports. This is in addition to

the $688 million Israeli industry is slated to receive from the Government of

Turkey for the upgrade of 170

M60A1 tanks. The potential exists for this number to rise to 900 Turkish

tanks, but only if the Merkava project is kept alive.48

Terminating the Merkava line would end any

hope of future overseas tank sales as well as the possibility of co-production

and licensing agreements on related technology. The shock to Israel’s defense

industries would be enormous, compounding an already serious decline in overseas

orders. In 2003, the country’s military exports fell by 37% from their high just

the year before.

At the present time, 220 companies supply

subcomponents to the IDF, the Merkava’s prime contractor. Of these firms, all

but a handful are Israeli. Approximately 22% of the Merkava’s content is of

American origin.

Israel's Merkava MK4 Main Battle Tank on Maneuvers

Source: Israeli-Weapons.com

In the event of a shutdown, between 6,500

and 10,000 workers could lose their jobs. Many of the affected companies reside

in development towns across Israel – from Kiryat Shemona in the north to Mitzpeh

Ramon in the south – where unemployment is high and the effects of the current

recession have hit hard.

It is unlikely that many of these workers,

many skilled in metal fabrication, electronics and systems integration, will

find alternative employment in a country already suffering from a saturated

labor market and massive cutbacks in its industrial sector. As a consequence, a

large number may seek jobs overseas, accelerating the flight of Israel’s

intellectual capital, slowing external investment and worsening the country’s

prospects for an economic recovery.

Many current and former IDF commanders have

criticized the government’s budget plan, noting that what is happening to the

Merkava is merely emblematic of a growing erosion in Israel’s overall national

security posture.

“These are unacceptable tradeoffs,”

observed Maj. Gen. Haim Erez (Res.).

The Merkava is the principal vehicle the

military has to seize and hold ground. Its design reflects decades of

operational experience, experience gained at a very high cost in lives and

money. Important, as well, is the fact that the effect of closing the program

will be felt throughout country’s defense industrial base. Israel’s economy will

suffer irrevocable damage as a result.49

Erez and his brigade were the first to

cross the Suez Canal during the 1973 Yom Kippur War in hot pursuit of the

retreating Egyptian Army.

Since its inception, Israel has spent

upwards of $6.5 billion in developing and acquiring the Merkava.

With the future of the Israeli tank program

in limbo, the MoD has shelved plans to develop the next generation armored

vehicle, the Merkava 5. Reports emanating from the IDF hint that the Army was

considering replacing the Merkava’s tracks with wheels in an effort to make it

faster, lighter and, in the view of some experts, more maneuverable.

Ultimately, though, salvation for the

Merkava may come about through the privatization of the main production line.

Talks are now underway between Israel Military Industries (IMI) and Urdan

Industries to purchase the Government’s interest in the program. An Urdan

subsidiary, Associated Steel Foundries of Netanya, is responsible for casting

many of the armored portions of the tank to include the turret, hull, tracks and

suspension. If concluded, this deal would permit the restructuring of the

program and the possibility of overseas sales.

Whether on the battlefield or in the

marketplace, the future success of the Merkava rests, for the foreseeable

future, on the commitment of the Israeli government to continue to modernize its tank

inventory. This means not only will Jerusalem need to make an ongoing investment

in tank technology, but it also must ensure that an economic rate of production

is maintained as well.

It takes approximately 30 months for a

fully operational Merkava tank to be assembled. Any hiatus in production funding

could have significant economic consequences for the companies responsible for

the program. Many have placed orders for long lead items with some, like the

American-made engine, extending out three years. Contract termination penalties

could run into the hundreds of millions of dollars.

At present, the IDF has

booked orders for the Merkava through 2007. With the current industrial base that will

require that the country manufacture between 60 and 70 Merkava Mk 4 tanks per

year. At this relatively modest rate of production and given Israel’s current

number of tanks that would means that a vehicle built today can be expected to

have a service life of between 50 and 80 years. By any reasonable standard, this

is an excessive amount of time for the fielding of a ground combat vehicle.

Abrams Alternative for Israel?

In place of the Merkava, some Israeli

government officials have suggested that Israel should consider adopting the

American M1 Abrams as its primary MBT. They argue that this would help to

standardize US and Israeli equipment and, in theory, allow Israel to divest

itself of a costly production line. An arrangement of this sort would probably

rest on an American commitment to allow Israel to incorporate its own

proprietary technology in its tanks.

Israel’s Finance Minister, Benjamin

Netanyahu, has lent his support to this idea and suggested further that the tanks

be paid for with the military assistance Jerusalem receives annually from the

US.50 With the recent defeat of the Iraqi army

and the removal of Saddam Hussein from power, Netanyahu contends that Israel no

longer needs such a large standing armor force to protect the country’s eastern

frontier.

Even so, there are at least six principal

reasons why Israel’s adoption of the Abrams M1 tank is impractical and, at the

present time, has little chance of succeeding.

A US Army Abrams M1A1 MBT in the Kuwaiti Desert

Source: SPG Media Ltd., 2004

First, the prime contractor for the M1,

General Dynamics Land Systems, no longer maintains a manufacturing line for the

tank. Restarting full-scale production at its Lima, Ohio facility would simply

be too costly and too impractical. It is more than likely the Pentagon would

oppose such a move as it focuses on developing a successor to the Abrams.

Second, the base cost for the M1 Abrams

tank is approximately $8-9 million against the cost of a new Merkava at

approximately $4-5 million. This price difference puts the Abrams out of reach

of the current Israeli defense budget plan.51

Third, a new heavy weapon system requires a

large support infrastructure for maintenance and repair. Here again cost is a

factor. Israel simply can not afford to have two parallel logistics tails for

its tank inventory. Besides the expense, it would only add to the difficultly of

providing fast and efficient support to armored units in wartime.52

Fourth, a well oiled production

infrastructure for the Merkava allows Israeli commanders to requisition spare

parts on an as-needed basis. Equipment lightly damaged in combat can be repaired

and quickly to returned to the field.

Fifth, Israel has learned through hard

experience that reliance on a foreign source of supply for spare parts for its

military significantly inhibits the country’s freedom of political action. With

dependency comes control. Successive generations of Israeli leaders have tried

to improve the self-sufficiency of the country’s military to lessen the amount

of leverage any third party has on the conduct of its foreign and military

policy.

At present, a joint venture between the

German firm MTU and GDLS is responsible for the production of the Merkava’s

GD883 diesel engine and Renk RK325 automatic transmission in the US. This had to

be done to circumvent an arms embargo imposed by Germany on Israel for its

actions taken in its war with the Palestinians.

Sixth, any Israeli purchase of Abrams tanks

would have to be made in dollars. Israel relies heavily on dollar denominated

foreign exchange for the purchase of essential overseas items from the US dollars are precious Treasury assets and always in short supply.

For the time

being, most of Israel’s military assistance dollars are committed to other

priority acquisition programs.

Either Israel would have to make funds

available out of its shrinking national budget to pay for the imported tanks – a

costly option – or it would have to earmark a portion of its US foreign

assistance for that purpose. Which ever choice Jerusalem would make, the

procurement would place an undue strain on the country’s finances and displace

other high-ticket programs vital to Israel’s national security.

Another advantage conferred by local

Merkava production is that Israel is able to finance much of its current content

using a portion of the US military aid package designated as Offshore

Procurement (OSP). These are funds that can be converted into shekels and spent

locally in Israel. Of the $2.33 billion in military

assistance provided by the US to Israel in 2004, $565 million, or 26%, may be

used for Offshore Procurement.53

These funds are critical to helping to maintain a strong defense industrial base

in Israel.

Even as the fate of the Merkava was being

decided, the IDF decided to go ahead with the decision to purchase the Stryker

armored vehicle. Cash starved and forced to cut back on essential training, the

Army nonetheless decided that it had the funds to launch an entirely new

procurement program. The $750 million price tag for the Stryker is to be paid

for using scarce US foreign assistance dollars.

Whereas most funds

spent on the Merkava are used domestically to boost the Israeli economy, those

spent on the Stryker are returned to the US and the prime contractor for the

system, General Dynamics.

Adopting a foreign weapons system as

important to Israel’s national defense as is the heavy tank would run contrary

to the goals of successive governments. With the harsh lessons of the 1973 Yom

Kippur War still fresh in the minds of many Israelis, few would have an interest

in returning to a time when Washington was able to stop an advancing Israeli

Army dead in its tracks simply because it controlled the supply of spare parts.

M1A2 Main Battle Tank firing its M256 main gun, a 120 mm smoothbore gun

developed by Rheinmetall GmbH of German

Source: SPG Media, Ltd., 2004

Another possibility is that Israel would

agree to exchange technology contained in the Merkava tank for a place on the

American team developing the replacement for the Abrams M1-A2 tank. Presumably

Israel would then have the right to supply components for the project and

eventually acquire the new vehicle, in quantity, for its own fleet.

According to reports that surfaced in late

2003, this idea was broached in talks between James Albaugh, the President of

Boeing Integrated Defense Systems, and Maj. Gen. Yiftah Ron Tal, Commander of IDF Ground Forces.54 Boeing is spearheading the

effort to design a new armored system as part of the Army’s Objective Force

strategy scheduled to become operational by 2010. The Future Combat Systems

program is intended to develop vehicles that are lighter, highly maneuverable

and more lethal than traditional heavy tanks while also being air transportable.

It may be some time before the Pentagon

decides if it will be allowed Israel to participate in new DoD effort. Equally

uncertain is whether the specifications for America’s future tank will coincide

with Israel’s requirements. The IDF, for instance, has no need to sacrifice

armor protection for air deployability.

Israel’s Worsening Budget Dilemma

The fact remains that the IDF has found it

impossible to fund many of its priority programs, not only the Merkava.

Equipment maintenance, training, the purchase of spare parts, research and

development (R&D), and the acquisition of new weapons

platforms have all been slashed in a bid to pay for current operations and

personnel costs. This state of affairs has become so severe that the IDF

announced at the start of 2004 that Army reservists would soon be training

without live ammunition because funds simply were not available to make the

necessary purchases.55

In some cases, reserve armor units have not received live training ammunition

for the past three years.

The situation is the same in the Navy and

Air Force where patrolling and flying hours also have been cut in an effort to

reduce training costs.56 According to one

report, the IDF is planning “to rent one of its training facilities to friendly

foreign armies” as one way of raising much needed revenue.57

This dramatic fall off in readiness has led

some military observers to conclude that the country is as ill prepared for

general war as it was in the months prior to conflict in 1973. If true, this is

a startling revelation and one which argues strenuously for an increase in

current Israeli defense spending. Commented Shaul Mofaz, the country’s Defense

Minister, “it could be that the security situation in 2004 will be worse than it

is now because of the fact that we will be unable to provide a security response

to threats.”58

In FY 2002, Israel’s defense spending was

cut by NIS 7 billion. In FY 2003 the reduction was NIS 2.25 billion.59

Today, Israel’s overall defense budget stands at roughly NIS 35.2 ($8.0 billion)

or about seven percent of GDP. By contrast, in 1984 Israel’s defense budget

stood at $11.3 billion or 24.5% of GDP.60 In

2004, approximately 13% of Israel’s state budget will be devoted to defense.

Additionally, the Ministry of Defense is

spending an estimated NIS 2 billion ($460 million) annually to quell the

Palestinian uprising.61 This figure does not

include the cost of constructing Israel’s security barrier or large scale

mobilizations like Operation Defensive Shield.

The Tank’s Tumultuous Future

For the foreseeable future, it would appear

the tank’s place on the modern Middle Eastern battlefield is secure. Yet, like

all military systems it will have to continue to evolve. A renaissance in heavy

armored systems may yet mark the tank’s future.

For the Israel soldiers who fought in the

Yom Kippur war of 1973, the tactical importance of the tank was proven

convincingly on both the Egyptian and Syrians fronts. After being routed from

their positions along the Suez Canal following Egypt’s surprise attack, a

battered Israeli army recovered from near defeat by employing superior armored

tactics backed by air cover. By the time the US brokered ceasefire took hold,

the Egyptian Third Army had been surrounded and its 45,000 men and 250 tanks

threatened with annihilation.

There are many lessons to be drawn from

this experience. The first of these is that Israel must not significantly

sacrifice quantity for quality in planning for future ground combat scenarios.

While there are many factors that contribute to victory in war – training,

tactics, superior equipment – it is also a fact that combat can not be sustained

on a high attrition battlefield without a sufficient reserve of men and

equipment.

Second, a robust industrial base for armor

should be maintained to support not only peacetime developmental efforts, but

also to serve as a source for the rapid delivery of spare parts and maintenance

activity in wartime.

Of the 2,000 tanks fielded by Israel during

the 1973 war, 400 were destroyed in combat. Many more were damaged, repaired and

returned to the fighting. By contrast, Egypt lost half of its armored force or

1,100 tanks out of an inventory of 2,200. Syrian losses amounted to 1,200 tanks

out of 1,820 pressed into service.62

As Israel’s economic situation weakens,

that of the Arab World appears to be improving. According to one economic

forecast, GDP in the Middle East and North Africa could reach 3.4% in real

growth in 2004.63 By contrast, Israel will be

lucky to achieve a 2.0% increase in its GDP during the same period. With a

growth rate of only 0.7% in 2003, Israel was ranked 24th out of 25

emerging economies by the British magazine,

The Economist.64

At the same time, military

spending throughout much of the Arab World

continues to grow.

If this trend persists, the Jewish state

could find itself matched by its potential enemies in both the quality and

quantity of military equipment at their disposal. This could pose a serious

readiness problem for a country that has striven, since 1967, for

self-sufficiency in most areas of its national defense.

And what does the future hold for the

Merkava? In a meeting with managers and workers at one of the main Merkava

facilities on December 23, 2003, Israeli Defense Minister Shaul Mofaz announced

that for the time being tank production would continue.

The Merkava is “vital to Israel’s

security”, he declared. “This is the flagship of the ground-based projects. This

project, like the rest of the defense industries, is an important strategic and

technological base for Israel and we can’t harm it.”65

Mofaz’s comments were echoed by the

Director General of Israel’s Ministry of Defense, Maj. Gen. Amos Yaron (ret.).

“This tank will continue to be built. Perhaps there will be difficulties in the

coming year; and perhaps we may need to decrease the number of tanks to be

produced, but this project will not stop. I repeat, this project will not end.”66

Addressing the role armor might play in the IDF of the future Yaron added: “The requirement for tanks remains, and the

requirement for the quality represented by the Merkava Mk 4 remains unchanged.

It is not possible to settle for less quality, and therefore this tank will

continue to be built.”67

These are certainly reassuring words to the

thousands of soldiers and workers whose lives and livelihoods depend upon

Israel’s commitment to heavy armor. Yet, without a new national consensus in

Israel on the need for increased defense expenditure, the upbeat assessment of

both Mofaz and Yaron may amount to little more than wishful thinking.